(Courtesy Special Collections Department, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa).

History Knows No Fences: An Overview

By John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth

As the centennial of Oklahoma statehood draws near, it is not difficult to look upon the history of our state with anything short of awe and wonder. In ninety-three short years, whole towns and cities have sprouted upon the prairies, great cultural and educational institutions have risen among the blackjacks, and the state's agricultural and industrial output has far surpassed even the wildest dreams of the Boomers. In less than a century, Oklahoma has transformed itself from a rawboned territory more at home in the nineteenth century, into now, as a new millennium dawns about us, a shining example of both the promise and the reality of the American dream. In looking back upon our past, we have much to take pride in.

But we have also known heartaches as well. As any honest history textbook will tell you, the first century of Oklahoma statehood has also featured dust storms and a Great Depression, political scandals and Jim Crow legislation, tumbling oil prices and truckloads of Okies streaming west. But through it all, there are two twentieth century tragedies which, sadly enough, stand head and shoulders above the others.

For many Oklahomans, there has never been a darker day than April 19, 1995. At two minutes past nine o'clock that morning, when the northern face of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City was blown inward by the deadliest act of terrorism ever to take place on American soil, lives were shattered, lives were lost, and the history of the state would never again be the same.

One-hundred-sixty-eight Oklahomans died that day. They were black and white, Native American and Hispanic, young and old. And during the weeks that followed, we began to learn a little about who they were. We learned about Colton and Chase Smith, brothers aged two and three, and how they loved their playmates at the daycare center. We learned about Captain Randy Guzman, U.S.M.C., and how he had commanded troops during Operation Desert Storm, and we learned about Wanda Lee Howell, who always kept a Bible in her purse. And we learned about Cartney Jean McRaven, a nineteen-year-old Air Force enlistee who had been married only four days earlier.

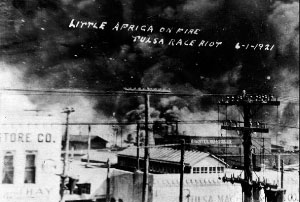

Perhaps more than anything else, what shocked most observers was the scope of the destruction in Tulsa. Practically the entire African

American district, stretching for more than a mile from Archer Street to the section line, had been reduced to a waste land of burned out

buildings, empty lots, and blackened trees (Courtesy Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa).

The Murrah Building bombing is, without any question, one of the great tragedies of Oklahoma history. And well before the last memorial service was held for the last victim, thousands of Oklahomans made it clear that they wanted what happened on that dark day to be remembered. For upon the chain-link fence surrounding the bomb site there soon appeared a makeshift memorial of the heart -- of teddy bears and handwritten children's prayers, key rings and dreamcatchers, flowers and flags. Now, with the construction and dedication of the Oklahoma City National Memorial, there is no doubt but that both the victims and the lessons of April 19, 1995 will not be forgotten.

But what would have come as a surprise to most of the state's citizens during the sad spring of 1995 was that there were, among them, other Oklahomans who carried within their hearts the painful memories of an equally dark, though long ignored, day in our past. For seventy-three years before the Murrah Building was bombed, the city of Tulsa erupted into a firestorm of hatred and violence that is perhaps unequaled in the peacetime history of the United States.

For those hearing about the 1921 Tulsa race riot for the first time, the event seems almost impossible to believe. During the course of eighteen terrible hours, more than one thousand homes were burned to the ground. Practically overnight, entire neighborhoods where families had raised their children, visited with their neighbors, and hung their wash out on the line to dry, had been suddenly reduced to ashes. And as the homes burned, so did their contents, including furniture and family Bibles, rag dolls and hand-me-down quilts, cribs and photograph albums. In less than twenty-four hours, nearly all of Tulsa's African American residential district -- some forty-square- blocks in all -- had been laid to waste, leaving nearly nine-thousand people homeless.

Gone, too, was the city's African American commercial district, a thriving area located along Greenwood Avenue which boasted some of the finest black-owned businesses in the entire Southwest. The Stradford Hotel, a modern fifty-four room brick establishment which housed a drug store, barber shop, restaurant and banquet hall, had been burned to the ground. So had the Gurley Hotel, the Red Wing Hotel, and the Midway Hotel. Literally dozens of family-run businesses--from cafes and mom-and-pop grocery stores, to the Dreamland Theater, the Y.M.C.A. Cleaners, the East End Feed Store, and Osborne Monroe's roller skating rink -- had also gone up in flames, taking with them the livelihoods, and in many cases the life savings, of literally hundreds of people.

<Image Not Available>

The Gurley Building prior to the riot (Courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center).

The offices of two newspapers -- the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun -- had also been destroyed, as were the offices of more than a dozen doctors, dentists, lawyers, realtors, and other professionals. A United States Post Office substation was burned, as was the all-black Frissell Memorial Hospital. The brand new Booker T. Washington High School building escaped the torches of the rioters, but Dunbar Elementary School did not. Neither did more than a half-dozen African American churches, including the newly constructed Mount Zion Baptist Church, an impressive brick tabernacle which had been dedicated only seven weeks earlier.

Harsher still was the human loss. While we will probably never know the exact number of people who lost their lives during the Tulsa race riot, even the most conservative estimates are appalling. While we know that the so-called "official" estimate of nine whites and twenty-six blacks is too low, it is also true that some of the higher estimates are equally dubious. All told, considerable evidence exists to suggest that at least seventy-five to one-hundred people, both black and white, were killed during the riot. It should be added, however, that at least one credible source from the period -- Maurice Willows, who directed the relief operations of the American Red Cross in Tulsa following the riot -- indicated in his official report that the total number of riot fatalities may have ran as high as three-hundred.1

(Courtesy of Greenwood Cultural Center).

We also know a little, at least, about who some of the victims were. Reuben Everett, who was black, was a laborer who lived with his wife Jane in a home along Archer Street. Killed by a gunshot wound on the morning of June 1, 1921, he is buried in Oaklawn Cemetery. George Walter Daggs, who was white, may have died as much as twelve hours earlier. The manager of the Tulsa office of the Pierce Oil Company, he was shot in the back of the bead as he fled from the initial gunplay of the riot that broke out in front of the Tulsa County Courthouse on the evening of May 31. Moreover, Dr. A. C. Jackson, a renowned African American physician, was fatally wounded in his front yard after he had surrendered to a group of whites. Shot in the stomach. He later died at the National Guard Armory. But for every riot victim's story that we know, there are others -- like the "unidentified Negroes" whose burials are recorded in the now yellowed pages of old funeral home ledgers -- whose names and life stories are, at least for now, still lost.

The destruction affected the African American business section and the residential neighborhoods in North Tulsa (Courtesy Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

By any standard, the Tulsa race riot of 1921 is one of the great tragedies of Oklahoma history. Walter White, one of the nation's foremost experts on racial violence, who visited Tulsa during the week after the riot, was shocked by what had taken place. "I am able to state," he said, "that the Tulsa riot, in sheer brutality and willful destruction of life and property, stands without parallel in America."2

Indeed, for a number of observers through the years, the term "riot" itself seems somehow inadequate to describe the violence and conflagration that took place. For some, what occurred in Tulsa on May 31 and June 1, 1921 was a massacre, a pogrom, or, to use a more modern term, an ethnic cleansing. For others, it was nothing short of a race war. But whatever term is used, one thing is certain: when it was all over, Tulsa's African American district had been turned into a scorched wasteland of vacant lots, crumbling storefronts, burned churches, and blackened, leafless trees.

Like the Murrah Building bombing, the Tulsa riot would forever alter life in Oklahoma. Nowhere, perhaps, was this more starkly apparent than in the matter of lynching. Like several other states and territories during the early years of the twentieth century, the sad spectacle of lynching was not uncommon in Oklahoma. In her 1942 master's thesis at the University of Oklahoma, Mary Elizabeth Estes determined that between the declaration of statehood on November 16, 1907, and the Tulsa race riot some thirteen years later, thirty-two individuals -- twenty-six of whom were black -- were lynched in Oklahoma. But during the twenty years following the riot, the number of lynchings statewide fell to two. Although they paid a terrible price for their efforts, there is little doubt except by their actions on May 31, 1921, that black Tulsans helped to bring the barbaric practice of lynching in Oklahoma to an end.

But unlike the Oklahoma City bombing, which has, to this day, remained a high profile event, for many years the Tulsa race riot practically disappeared from view. For decades afterwards, Oklahoma newspapers rarely mentioned the riot, the state's historical establishment essentially ignored it, and entire generations of Oklahoma school children were taught little or nothing about what had happened. To be sure, the riot was still a topic of conversation, particularly in Tulsa. But these discussions -- whether among family or friends, in barber shops or on the front porch -- were private affairs. And once the riot slipped from the headlines, its public memory also began to fade.

Of course, anyone who lived through the riot could never forget what had taken place. And in Tulsa's African American neighborhoods, the physical, psychological, and spiritual damage caused by the riot remained highly apparent for years. Indeed, even today there are places in the city where the scars of the riot can still be observed. In North Tulsa, the riot was never forgotten -- because it could not be.

But in other sections of the city, and elsewhere throughout the state, the riot slipped further and further from view. And as the years passed and, particularly after World War II, as more and more families moved to Oklahoma from out-of-state, more and more of the state's citizens had simply never heard of the riot. Indeed, the riot was discussed so little, and for so long, even in Tulsa, that in 1996, Tulsa County District Attorney Bill LaFortune could tell a reporter, "I was born and raised here, and I had never heard of the riot."4

How could this have happened? How could a disaster the size and scope of the Tulsa race riot become, somehow, forgotten? How could such a major event in Oklahoma history become so little known?

Some observers have claimed that the lack of attention given to the riot over the years was the direct result of nothing less than a "conspiracy of silence." And while it is certainly true that a number of important documents relating to the riot have turned up missing, and that some individuals are, to this day, still reluctant to talk about what happened, the shroud of silence that descended over the Tulsa race riot can also be accounted for without resorting to conspiracy theories. But one must start at the beginning.

The riot, when it happened, was front-page news across America. "85 WHITES AND NEGROES DIE IN TULSA RIOTS" ran the headline in the June 2, 1921 edition of the New York Times, while dozens of other newspapers across the country published lead stories about the riot. Indeed, the riot was even news overseas, "FIERCE OUTBREAK IN OKLAHOMA" declared The Times of London.5

But something else happened as well. For in the days and weeks that followed the riot, editorial writers from coast-to-coast unleashed a torrent of stinging condemnations of what had taken place. "The bloody scenes at Tulsa, Oklahoma," declared the Philadelphia Bulletin, "are hardly conceivable as happening in American civilization of the present day." For the Kentucky State Journal, the riot was nothing short of "An Oklahoma Disgrace," while the Kansas City Journal was revolted at what it called the "Tulsa Horror". From both big-city dailies and small town newspapers -- from the Houston Post and Nashville Tennessean to the tiny Times of Gloucester, Massachusetts -- came a chorus of criticism. The Christian Recorder even went so far as to declare that "Tulsa has become a name of shame upon America."6

For many Oklahomans, and particularly for whites in positions of civic responsibility, such sentiments were most unwelcome. For regardless of what they felt personally about the riot, in a young state where attracting new businesses and new settlers was a top priority, it soon became evident that the riot was a public relations nightmare. Nowhere was this felt more acutely than in Tulsa. "I suppose Tulsa will get a lot of unpleasant publicity from this affair," wrote one Tulsa-based petroleum geologist to family members back East. Reverend Charles W. Kerr, of the city's all-white First Presbyterian Church, added his own assessment. "For 22 years I have been boosting Tulsa," he said, "and we have all been boosters and boasters about our buildings, bank accounts and other assets, but the events of the past week will put a stop to the bragging for a while."7 For some, and particularly for Tulsa's white business and political leaders, the riot soon became something best to be forgotten, something to be swept well beneath history's carpet.

What is remarkable, in retrospect, is the degree to which this nearly happened. For within a decade after it had happened, the Tulsa race riot went from being a front-page, national calamity, to being an incident portrayed as an unfortunate, but not really very significant, event in the state's past. Oklahoma history textbooks published during the 1920s did not mention the riot at all -- nor did ones published in the 1930s. Finally, in 1941, the riot was mentioned in the Oklahoma volume in the influential American Guide Series -- but only in one brief paragraph.8

Despite the aid given by the Red Cross, black Tulsans faced a gargantuan task in the rebuilding of Greenwood. Literally thousands were forced to spend the winter of 1921-22 living in tents (Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society).

Nowhere was this historical amnesia more startling than in Tulsa itself, especially in the city's white neighborhoods. "For a while," noted former Tulsa oilman Osborn Campbell, "picture postcards of the victims in awful poses were sold on the streets," while more than one white ex-rioter "boasted about how many notches be bad on his gun." But the riot, which some whites saw as a source of local pride, in time more generally came to be regarded as a local embarrassment. Eventually, Osborn added, "the talk stopped."9

So too, apparently did the news stories. For while it is highly questionable whether -- as it has been alleged -- any Tulsa newspaper actually discouraged its reporters from writing about the riot, for years and years on end the riot does not appear to have been mentioned in the local press.10 And at least one local paper seems to have gone well out of its way, at times, to avoid the subject altogether.

During the mid-1930s, the Tulsa Tribune -- the city's afternoon daily newspaper -- ran a regular feature on it editorial page called "Fifteen Years Ago." Drawn from back issues of the newspaper, the column highlighted events which had happened in Tulsa on the same date fifteen years earlier, including local news stories, political tidbits, and society gossip. But when the fifteenth anniversary of the race riot arrived in early June, 1936, the Tribune ignored it completely -- and instead ran the following:

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO

Miss Carolyn Skelly was a charming young hostess of the past week, having entertained at a luncheon and theater party for Miss Kathleen Sinclair and her guest, Miss Julia Morley of Saginaw, Mich. Corsage bouquets of Cecil roses and sweet peas were presented to the guests, who were Misses Claudine Miller, Martha Sharpe, Elizabeth Cook, Jane Robinson, Pauline Wood, Marie Constantin, Irene Buel, Thelma Kennedy, Ann Kennedy, Naomi Brown, Jane Wallace and Edith Smith.

Mrs. O.H.P. Thomas will entertain for her daughter, Elizabeth, who has been attending Randolph Macon school in Lynchburg, Va.

Central high school's crowning social event of the term just closed was the senior prom in the gymnasium with about 200 guests in attendance. The grand march was led by Miss Sara Little and Seth Hughes.

Miss Vera Gwynne will leave next week for Chicago to enter the University of Chicago where she will take a course in kindergarten study.

Mr. And Mrs. E.W. Hance have as their guests Mr. L.G. Kellenneyer of St. Mary's, Ohio.

Mrs. C.B. Hough and her son, Ralph, left last night for a three-months trip through the west and northwest. They will return home via Dallas, Texas, where they will visit Mrs. Hough's homefolk.11

Ten years later, in 1946, by which time the Tribune had added a "Twenty-Five Years Ago" feature, the newspaper once again avoided mentioning the riot. It was as if the greatest catastrophe in the city's history simply had not happened at all.12

That there would be some reluctance toward discussing the riot is hardly surprising. Cities and states -- just like individuals -- do not, as a general rule, like to dwell upon their past shortcomings. For years and years, for example, Oklahoma school children were taught only the most sanitized versions of the story of the Trail of Tears, while the history of slavery in Oklahoma was more or less ignored altogether. Moreover, during the World War II years, when the nation was engaged in a life or death struggle against the Axis, history textbooks quite understandably stressed themes of national unity and consensus. The Tulsa race riot, needless to say, did not qualify.

Dedication of the black wallstreet memorial in 1996 attended by Robert Fairchild (Courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center).

But in Tulsa itself, the riot had affected far too many families, on both sides of the tracks, ever to sink entirely from view. But as the years passed and the riot grew ever more distant, a mindset developed which held that the riot was one part of the city's past that might best be forgotten altogether. Remarkably enough, that is exactly what began to happen.

When Nancy Feldman moved to Tulsa during the spring of 1946, she had never heard of the Tulsa race riot. A Chicagoan, and a new bride, she accepted a position teaching sociology at the University of Tulsa. But trained in social work, she also began working with the City Health Department, where she came into contact with Robert Fairchild, a recreation specialist who was also one of Tulsa's handful of African American municipal employees. A riot survivor, Fairchild told Feldman of his experiences during the disaster, which made a deep impression on the young sociologist, who decided to share her discovery with her students.13

But as it turned out, Feldman also soon learned something else, namely, that learning about the riot, and teaching about it, were two entirely different propositions. "During my first months at TU," she later recalled:

I mentioned the race riot in class one day and was surprised at the universal surprise among my students. No one in this all- white classroom of both veterans, who were older, and standard 18-year-old freshmen, had ever heard of it, and some stoutly denied it and questioned my facts.

I invited Mr. Fairchild to come to class and tell of his experience, walking along the railroad tracks to Turley with his brothers and sister. Again, there was stout denial and, even more surprising, many students asked their parents and were told, no, there was no race riot at all. I was called to the Dean's office and advised to drop the whole subject.

The next semester, I invited Mr. Fairchild to come to class. Several times the Dean warned me about this. I do not believe I ever suffered from this exercise of my freedom of speech . . . but as a very young and new instructor, I certainly felt threatened.

For Feldman, such behavior amounted to nothing less than "Purposeful blindness and memory blocking." Moreover, she discovered, it was not limited to the classroom. "When I would mention the riot to my white friends, few would talk about it. And they certainly didn't want to."14

While perhaps surprising in retrospect, Feldman's experiences were by no means unique. When Nancy Dodson, a Kansas native who later taught at Tulsa Junior College, moved to Tulsa in 1950, she too discovered that, at least in some parts of the white community, the riot was a taboo subject. "I was admonished not to mention the riot almost upon our arrival," she later recalled, "Because of shame, I thought. But the explanation was 'you don't want to start another.'"15

The riot did not fare much better in local history efforts. While Angie Debo did make mention of the riot in her 1943 history, Tulsa: From Creek Town to Oil Capital, her account was both brief and superficial. And fourteen years later, during the summer of 1957, when the city celebrated its "Tulsarama" - a week-long festival commemorating the semi-centennial of Oklahoma statehood -- the riot was, once again, ignored.16 Some thirty-five years after it had taken the lives of dozens of innocent people, destroyed a neighborhood nearly one-square-mile in size in a firestorm which sent columns of black smoke billowing hundreds of feet into the air, and brought the normal life of the city to a complete standstill, the Tulsa race riot was fast becoming little more than a historical inconvenience, something, perhaps, that ought not be discussed at all.

Despite such official negligence, however, there were always Tulsans through the years who helped make it certain that the riot was not forgotten. Both black and white, sometimes working alone but more often working together, they collected evidence, preserved photographs, interviewed eyewitnesses, wrote about their findings, and tried, as best as they could, to ensure that the riot was not erased from history.

None, perhaps, succeeded as spectacularly as Mary E. Jones Parrish, a young African American teacher and journalist. Parrish had moved to Tulsa from Rochester, New York in 1919 or 1920, and had found work teaching typing and shorthand at the all-black Hunton Branch of the Y.M.C.A.. With her young daughter, Florence Mary, she lived at the Woods Building in the heart of the African American business district. But when the riot broke out, both mother and daughter were forced to abandon their apartment and flee for their lives, running north along Greenwood Avenue amid a hail of bullets.17

Immediately following the riot, Parrish was hired by the Inter-Racial Commission to "do some reporting" on what had happened. Throwing herself into her work with her characteristic verve -- and, one imagines, a borrowed typewriter -- Parrish interviewed several eyewitnesses and transcribed the testimonials of survivors. She also wrote an account of her own harrowing experiences during the riot and, together with photographs of the devastation and a partial roster of property losses in the African American community, Parrish published all of the above in a book called Events of the Tulsa Disaster. And while only a handful of copies appear to have been printed, Parrish's volume was not only the first book published about the riot, and a pioneering work of journalism by an African American woman, but remains, to this day, an invaluable contemporary account.18

It took another twenty-five years, however, until the first general history of the riot was written. In 1946, a white World War II veteran named Loren L. Gill was attending the

University of Tulsa. Intrigued by lingering stories of the race riot, and armed with both considerable energy and estimable research skills, Gill decided to make the riot the subject of his master's thesis.19

The end result, "The Tulsa Race Riot," was, all told, an exceptional piece of work, Gill worked diligently to uncover the causes of the riot, and to trace its path of violence and destruction, by scouring old newspaper and magazine articles, Red Cross records, and government documents. Moreover, Gill interviewed more than a dozen local citizens, including police and city officials, about the riot. And remarkably for the mid-1940's, Gill also interviewed a number of African American riot survivors, including Reverend Charles Lanier Netherland, Mrs. Dimple L. Bush, and the noted attorney, Amos T. Hall. And while a number of Gill's conclusions about the riot have not withstood subsequent historical scrutiny, few have matched his determination to uncover the truth.20

Yet despite Gill's accomplishment, the riot remained well-buried in the city's historical closet. Riot survivors, participants, and observers, to be certain, still told stories of their experiences to family and friends. And at Tulsa's Booker T. Washington High School, a handful of teachers made certain that their students -- many of whose families had moved to Tulsa after 1921 -- learned at least a little about what had happened. But the fact remains that for nearly a quarter of a century after Loren Gill completed his master's thesis, the Tulsa race riot remained well out of the public spotlight.21

But beneath the surface, change was afoot. For as the national debate over race relations intensified with the emergence of the modem civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Tulsa's own racial customs were far from static. As the city began to address issues arising out of school desegregation, sit-ins, job bias, housing discrimination, urban renewal, and white flight, there were those who believed that Tulsa's racial past -- and particularly the race riot -- needed to be openly confronted.

Few felt this as strongly as those who had survived the tragedy itself, and on the evening of June 1, 1971, dozens of African American riot survivors gathered at Mount Zion Baptist Church for a program commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the riot. Led by W.D. Williams, a longtime Booker T. Washington High School history teacher, whose family had suffered immense property loss during the violence, the other speakers that evening included fellow riot survivors Mable B. Little, who had lost both her home and her beauty shop during the conflagration, and E.L. Goodwin, Sr., the publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle, the city's black newspaper. Although the audience at the ceremony -- which included a handful of whites -- was not large, the event represented the first public acknowledgment of the riot in decades.22

But another episode that same spring also revealed just how far that Tulsa, when it came to owning up to the race riot, still had to go. The previous autumn, Larry Silvey, the publications manager at the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, decided that on the fiftieth anniversary of the riot, the chamber's magazine should run a story on what had happened. Silvey then contacted Ed Wheeler, the host of 'The Gilcrease Story," a popular history program which aired on local radio. Wheeler -- who, like Silvey, was white -- agreed to research and write the article. Thus, during the winter of 1970-71, Wheeler went to work, interviewing dozens of elderly black and white riot eyewitnesses, and searching through archives in both Tulsa and Oklahoma City for documents pertaining to the riot.23

But something else happened as well. For on two separate occasions that winter, Wheeler was approached by white men, unknown to him, who warned him, "Don't write that story." Not long thereafter, Wheeler's home telephone began ringing at all hours of the day and night, and one morning he awoke to find that someone had taken a bar of soap and scrawled across the front windshield of his car, "Best check under your hood from now on."

But Ed Wheeler was a poor candidate for such scare tactics. A former United States Army infantry officer, the incidents only angered him. Moreover, he was now deep into trying to piece together the history of the riot, and was not about to be deterred. But to be on the safe side, he sent his wife and young son to live with his mother-in-law. 24

Despite the harassment, Wheeler completed his article and Larry Silvey was pleased with the results. However, when Silvey began to lay out the story -- complete with never-before- published photographs of both the riot and its aftermath chamber of commerce management killed the article. Silvey appealed to the chamber's board of directors, but they, too, refused to allow the story to be published.

Determined that his efforts should not have been in vain, Wheeler then tried to take his story to Tulsa's two daily newspapers, but was rebuffed. In the end, his article -- called "Profile of a Race Riot" -- was published in Impact Magazine, a new, black-oriented publication edited by a young African American journalist named Don Ross.

Representative Don Ross at Greenwood and Archer (Courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center).

"Profile of a Race Riot" was a hand-biting, path-breaking story, easily the best piece of writing published about the riot in decades. But is was also a story whose impact was both limited and far from citywide. For while it has been reported that the issue containing Wheeler's story sold out "virtually overnight," the magazine's readership, which was not large to begin with, was almost exclusively African American. Ultimately, "Profile of a Race Riot" marked a turning point in how the riot would be written about in the years to come, but at the time that it was published, few Tulsans -- and hardly any whites -- even knew of its existence.25

One of the few who did was Ruth Sigler Avery, a white Tulsa woman with a passion for history. A young girl at the time of the riot, Avery had been haunted by her memories of the smoke and flames rising up over the African American district, and by the two trucks carrying the bodies of riot victims that had passed in front of her home on East 8th Street.

Determined that the history of the riot needed to be preserved, Avery begin interviewing riot survivors, collecting riot photographs, and serving as a one-woman research bureau for anyone interested in studying what had happened. Convinced that the riot had been deliberately covered-up, Avery embarked upon what turned out to be a decades-long personal crusade to see that the true story of the riot was finally told.26

Along the way, Avery met some kindred spirits -- and none more important that Mozella Franklin Jones. The daughter of riot survivor and prominent African American attorney Buck Colbert Franklin, Jones had long endeavored to raise awareness of the riot particularly outside of Tulsa's black community. While she was often deeply frustrated by white resistance to confronting the riot, her accomplishments were far from inconsequential. Along with Henry C. Whitlow, Jr., a history teacher at Booker T. Washington High School, Jones had not only helped to desegregate the Tulsa Historical Society, but had mounted the first-ever major exhibition on the history of African Americans in Tulsa. Moreover, she had also created, at the Tulsa Historical Society, the first collection of riot photographs available to the public.27

None of these activities, however, was by itself any match for the culture of silence which had long hovered over the riot, and for years to come, discussions of the riot were often curtailed. Taken together, the fiftieth anniversary ceremony, "Profile of a Race Riot," and the work of Ruth Avery and Mozella Jones had nudged the riot if not into the spotlight, then at least out of the back reaches of the city's historical closet.28

Moreover, these local efforts mirrored some larger trends in American society. Nationwide, the decade of the 1970s witnessed a virtual explosion of interest in the African American experience. Millions of television viewers watched Roots, the miniseries adaptation of Alex Haley's chronicle of one family's tortuous journey through slavery, while books by black authors climbed to the top of the bestseller lists. Black studies programs and departments were created at colleges from coast-to-coast, while at both the high school and university level, teaching materials began to more fully address issues of race. As scholars started to re-examine the long and turbulent history of race relations in American -- including racial violence -- the Tulsa riot began to receive some limited national exposure .29

Similar activities took place in Oklahoma. Kay M. Teall's Black History in Oklahoma, an impressive collection of historical documents published in 1971, helped to make the history of black Oklahomans far more accessible to teachers across the state. Teall's book paid significant attention to the story of the riot, as did Arthur Tolson's The Black Oklahomans: A History 1541-1972, which came out one year later.30

In 1975, Northeastern State University historian Rudia M. Halliburton, Jr. published The Tulsa Race War of 1921. Adapted from an article he had published three years earlier in the Journal of Black Studies, Halliburton's book featured a remarkable collection of riot photographs, many of which he had collected from his students. Issued by a small academic press in California, Halliburton's book received little attention outside of scholarly circles. Nonetheless, as the first book about the riot published in more than a half-century, it was another important step toward unlocking the riot's history.31

In the end, it would still take several years -- and other books, and other individuals -- to lift the veil of silence fully which bad long hovered over the riot. However, by the end of the 1970s, efforts were underway that, once and for all, would finally bring out into the open the history of the tragic events of the spring of 1921.32

Today, the Tulsa race not is anything but unknown.

During the past two years, both the riot itself, and the efforts of Oklahomans to come to terms with the tragedy, have been the subject of dozens of magazine and newspaper articles, radio talk shows, and television documentaries. In an unprecedented and continuing explosion of press attention, journalists and film crews from as far away as Paris, France and London, England have journeyed to Oklahoma to interview riot survivors and eyewitnesses, search through archives for documents and photographs, and walk the ground where the killings and burning of May 31 and June 1, 1921 took place.

After years of neglect, stories and articles about the riot have appeared not only in Oklahoma magazines and newspapers, but also in the pages of the Dallas Morning News, The Economist, the Kansas City Star, the London Daily Telegraph, the Los Angeles Times, the National Post of Canada, the New York Times, Newsday, the Philadelphia Inquirer, US. News and World Report, USA Today, and the Washington Post. The riot has also been the subject of wire stories issued by the Associated Press and Reuter's. In addition, news stories and television documentaries about the riot have been produced by ABC News Nightline, Australian Broadcasting, the BBC, CBS News' 60 Minutes II, CNN, Cinemax, The History Channel, NBC News, National Public Radio, Norwegian Broadcasting, South African Broadcasting, and Swedish Broadcasting, as well as by a number of in-state television and radio stations. Various web sites and Internet chat rooms have also featured the riot, while in numerous high school and college classrooms across America, the riot has become a subject of study. All told, for the first time in nearly eighty years, the Tulsa race riot of 1921 has once again become front-page news.33

What has not made the headlines, however, is that for the past two-and-one-half years, an intensive effort has been quietly underway to investigate, document, analyze, and better understand the history of the riot. Archives have been searched through, old newspapers and government records have been studied, and sophisticated, state-of-the-art scientific equipment has been utilized to help reveal the potential location of the unmarked burial sites of riot victims. While literally dozens of what appeared to be promising leads for reliable new information about the riot turned out to be little more than dead ends, a significant amount of previously unavailable evidence -- including long-forgotten documents and photographs -- has been discovered.

None of this, it must be added, could have been possible without the generous assistance of Oklahomans from all walks of life. Scores of senior citizens -- including riot survivors and observers, as well as the sons and daughters of policemen, National Guardsmen, and riot participants have helped us to gain a much clearer picture of what happened in Tulsa during the spring of 1921. All told, literally hundreds of Oklahomans, of all races, have given of their time, their memories, and their expertise to help us all gain a better understanding of this great tragedy.

This report is a product of these combined efforts. The scholars who have written it are all Oklahomans -- either by birth, upbringing, residency, or family heritage. Young and not-so-young, black and white, men and women, we include within our ranks both the grandniece and the son of African American riot survivors, as well as the son of a white eyewitness. We are historians and archaeologists, forensic scientists and legal scholars, university professors and retirees,

For the editors of this report, the riot also bears considerable personal meaning. Tulsa is our hometown, and we are both graduates of the Tulsa Public Schools. And although we grew up in different eras, and in different parts of town -- and heard about the riot, as it were, from different sides of the fence -- both of our lives have been indelibly shaped by what happened in 1921.

History knows no fences. While the stories that black Oklahomans tell about the riot often differ from those of their white counterparts, it is the job of the historian to locate the truth wherever it may lie. There are, of course, many legitimate areas of dispute about the riot -- and will be, without a doubt, for years to come. But far more significant is the tremendous amount of information that we now know about the tragedy -- about how it started and how it ended, about its terrible fury and its murderous violence, about the community it devastated and the lives it shattered. Neither myth nor "confusion", the riot was an actual, definable, and describable event. In Oklahoma history, the central truths of which can, and must, be told.

That won't always be easy. For despite the many acts of courage, heroism, and selflessness that occurred on May 31 and June 1, 1921 -- some of which are described in the pages that follow -- the story of the Tulsa race riot is a chronicle of hatred and fear, of burning houses and shots fired in anger, of justice denied and dreams deferred. Like the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building some seventy-three years later, there is simply no denying the fact that the riot was a true Oklahoma tragedy, perhaps our greatest.

But, like the bombing, the riot can also be a bearer of lessons -- about not only who we are, but also about who we would like to be. For only by looking to the past can we see not only where we have been, but also where we are going. And as the first one-hundred years of Oklahoma statehood draws to a close, and a new century begins, we can best honor that past not by burying it, but by facing it squarely, honestly, and, above all, openly.

Endnotes

1

For the so-called "official" estimate, see: Memorandum from Major Paul R. Brown, Surgeon, 3rd Infantry, Oklahoma National Guard, to the Adjutant General of Oklahoma, June 4, 1921, located in the Attorney Generals Civil Case Files, Record Group 1-2, Case 1062, State Archives Division, Oklahoma Department of Libraries.For the Maurice Willows estimates, see: "Disaster Relief Report, Race Riot, June 1921," p. 6, reprinted in Robert N. Hower, "Angels of Mercy": The American Red Cross and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot (Tulsa: Homestead Press, 1993).

2

New York Call, June 10, 1921.3

Mary Elizabeth Estes, "An Historical Survey of Lynchings in Oklahoma and Texas" (M.A. thesis, University of Oklahoma, 1942), pp. 132-1344

Jonathan Z. Larsen, "Tulsa Burning," Civilization, IV, I (February/March 1997), p. 46.5

New York Times, June 2, 1921, p. 1. [London, England] The Times, June 2, 1921, p. 10.6

Philadelphia Bulletin, June 3, 1921. [Frankfort] Kentucky State Journal, June 5, 1921. "Mob Fury and Race Hatred as a National Disgrace," Literary Digest, June 18, 1921, pp. 7-9. R.R. Wright, Jr., "Tulsa," Christian Recorder, June 9, 1921.7

The geologist, Robert F. Truex, was quoted in the Rochester [New York] Herald, June 4, 1921. The Kerr quote is from "Causes of Riots Discussed in Pulpits of Tulsa Sunday," an unattributed June 6, 1921 article located in the Tuskegee Institute News Clipping File, microfilm edition, Series 1, "1921 -- Riots, Tulsa, Oklahoma, " Reel 14, p. 754.8

Joseph P. Thoburn and Muriel H. Wright, Oklahoma: A History of the State and Its People (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing, 1929). Muriel H. Wright, The Story of Oklahoma (Oklahoma City: Webb Publishing Company, 1929-30). Edward Everett Dale and Jesse Lee Rader, Readings in Oklahoma History (Evanston, Illinois: Row, Peterson and Company, 1930). Victor E. Harlow, Oklahoma: Its Origins and Development (Oklahoma City: Harlow Publishing Company, 1935). Muriel H. Wright, Our Oklahoma (Guthrie: Co-operative Publishing Company, 1939). [Oklahoma Writers' Project] Oklahoma: A Guide to the Sooner State (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941), pp. 208-209.9

Osborn Campbell, Let Freedom Ring (Tokyo: Inter-Nation Company, 1954), p. 175.10

In 197 1, a Tulsa Tribune reporter wrote that, "For 50 years The Tribune did not rehash the story [of the riot]." See: "Murderous Race Riot Wrote Red Page in Tulsa History 50 Years Ago," Tulsa Tribune, June 2, 1971, p. 7A. A very brief account of the riot that not only gave the wrong dates for the conflict, but also claimed that "No one knew then or remembers how the shooting began--appeared in the Tulsa World on November 7, 1949.On the reluctance of the local press to write about the riot, see: Brent Stapes, "Unearthing a Riot" New York Times Magazine, December 19, 1999, p. 69; and, oral history interview with Ed Wheeler, Tulsa, February 27, 1998, by Scott Ellsworth.

11

Tulsa Tribune, June 2, 1936, p. 1612

Ibid., May 31, 1946, p. 8; and June 2, 1946, p. 8.The Tulsa World, to its credit, did mention the riot in its "Just 30 Years Ago" columns in 1951. Tulsa World. June 1, 1951, p. 20; June 2, 1951, p. 4; and June 4, 1951, p. 6.

13

Telephone interview with Nancy Feldman, Tulsa, July 17, 2000. Letter from Nancy G. Feldman, Tulsa, July 19, 2000, to Dr. Bob Blackburn, Oklahoma City.On Robert Fairchild see: Oral History Interview with Robert Fairchild, Tulsa, June 8, 1978, by Scott Ellsworth, a copy of which can be found in the Special Collections Department, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa; and, Eddie Faye Gates, They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa (Austin: Eakin Press, 1997), pp. 69-72.

14

Feldman letter, op cit.15

Letter from Nancy Dodson, Tulsa, June 4, 2000, to John Hope Franklin, Durham, North Carolina.16

Angie Debo, Tulsa: From Creek Town to Oil Capital (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1943).On the "Tulsarama," see: Bill Butler, ed., "Tulsarama! Historical Souvenir Program," and Quentin Peters, "Tulsa, I.T.," two circa-1957 pamphlets located in the Tulsa history vertical subject files at the Oklahoma Historical Society library, Oklahoma City.

17

Mary E. Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster (N.p., n.p., n.d.). in 1998. A reprint edition of Parrish's book was published by Out on a Limb Publishing in Tulsa.Tulsa City Directory, 1921 (Tulsa: Polk-Hoffhine Directory Company, 1921).

18

Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster (rpt. ed.; Tulsa: Out on a Limb Publishing, 1998), pp. 27, 31-77, 115-126.Prior to the publication of Parrish's book, however, a "booklet about the riot was issued by the Black Dispatch Press of Oklahoma City in July, 1921. Written by Martin Brown, the booklet was titled, "Is Tulsa Sane?" At present, no copies are known to exist.

19

Loren L. Gill, "The Tulsa Race Riot" (M.A. thesis, University of Tulsa, 1946).20

Ibid. According to his thesis adviser, William A. Settle, Jr., Gill was later highly critical of some of his original interpretations. During a visit to Tulsa during the late 1960s, after he had served as a Peace Corps volunteer, Gill told Settle that he bad been "too hard" on black Tulsans.21

Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (BatonRouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982), pp. 104-107. Gina Henderson and Marlene L. Johnson, "Black Wall Street," Emerge, ) 4 (February, 2000), p. 71.

The lack of public recognition given to the riot during this period was not limited to Tulsa's white community. A survey of back issues of the Oklahoma Eagle -- long the city's flagship African American newspaper -- revealed neither any articles about the riot, nor any mention of any commemorative ceremonies, at the time of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the riot in 1946. The same also applied to the thirtieth and fortieth anniversaries in 1951 and 1961.

22

Oklahoma Eagle, June 2, 197 1, pp. 1, 10. Tulsa Tribune, June 2, 197 1, p. 7A. Sam Howe Verhovek, "75 Years Later, Tulsa Confronts Its Race Riot," New York Times, May 31, 1996, p. 12A. Interview with E.L. Goodwin, Sr., Tulsa, November 21, 1976, in Ruth Sigler Avery, Fear: The Fifth Horseman -- A Documentary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, unpublished manuscript.See also: Mable B. Little, Fire on Mount Zion: My Life and History as a Black Woman in American (Langston, OK: The Black Think Tank, 1990); Beth Macklin, "'Home' Important in Tulsan's Life," Tulsa World, November 30, 1975, p. 3H; and Mable B. Little, "A History of the Blacks of North Tulsa and My Life (A True Story)," typescript dated May 24, 1971.

23

Telephone interview with Larry Silvey, Tulsa, August 5, 1999. Oral history interview with Ed Wheeler, Tulsa, February 27, 1998, by Scott Ellsworth. See also: Brent Stapes, "Unearthing a Riot, " New York Times Magazine, December 19, 1999, p. 69.24

Ed Wheeler interview.25

Ibid. Larry Silvey interview. Ed Wheeler, "Profile of a Race Riot," Impact Magazine, IV (June-July 197 1). Staples, "Unearthing a Riot," p. 69.26

Avery, Fear: The Fifth Horseman. William A. Settle, Jr. and Ruth S. Avery, "Report of December 1978 on the Tulsa County Historical Society's Oral History Program," typescript located at the Tulsa Historical Society. Telephone interview with Ruth Sigler Avery, Tulsa, September 14, 2000.27

Mozella Jones Collection, Tulsa Historical Society. John Hope Franklin and John Whittington Franklin, eds., My Life and An Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997). John Hope Franklin, "Tulsa: Prospects for a New Millennium," remarks given at Mount Zion Baptist Church, Tulsa, June 4, 2000.Whitlow also was an authority on the history of Tulsa's African American community. See: Henry C. Whitlow, Jr., "A History of the Greenwood Era in Tulsa," a paper presented to the Tulsa Historical Society, March 29, 1973.

28

During this same period, a number of other Tulsans also endeavored to bring the story of the riot out into the open. James Ault, who taught sociology at the University of Tulsa during the late 1960s, interviewed a number of riot survivors and eyewitnesses. So did Bruce Hartnitt, who directed the evening programs at Tulsa Junior College during the early 1970s. Harnitt's father, who had managed the truck fleet at a West Tulsa refinery at the time of the riot, later told his son that he had been ordered to help transport the bodies of riot victims.Telephone interview with James T. Ault, Omaha, Nebraska, February 22, 1999. Oral history interview with Bruce Hartnitt, Tulsa, May 30, 1998, by Scott Ellsworth.

29

John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, 7th edition (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 476. Richard Maxwell Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975). Lee E. Williams and Lee. E. Williams 11, Anatomy of Four Race Riots: Racial Conflict in Knoxville, Elaine (Arkansas), Tulsa and Chicago, 1919-1921 (Hattiesburg: University and College Press of Mississippi, 1972).30

Kay M.Teall, ed., Black History in Oklahoma: A Resource Book (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma City Public Schools, 1971). Arthur Tolson, The Black Oklahomans: A History, 1541-1972 (New Orleans: Edwards Printing Company, 1972).31

Rudia M. Halliburton, Jr., The Tulsa Race War of 1921 (San Francisco: R and E Research Associates, 1975).32

Following the publication of Scott Ellsworth's Death in a Promised Land in 1982, a number of books have been published which deal either directly or indirectly with the riot. Among them are: Mabel B. Little, Fire on Mount Zion (1990); Robert N. Hower, "Angels of Mercy": The American Red Cross and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot (Tulsa: Homestead Press, 1993); Eddie Faye Gates, They Came Searching (1997); Dorothy Moses DeWitty, Tulsa: A Tale of Two Cities (Langston, OK: Melvin B. Tolson Black Heritage Center, 1997); Danney Goble, Tulsa!: Biography of the American City (Tulsa: Council Oak Books, 1997); and, Hannibal B. Johnson, Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa's Historic Greenwood District (Austin: Eakin Press, 1998).The riot has inspired some fictionalized treatments as well, including: Ron Wallace and J.J. Johnson, Black Wall Street. A Lost Dream (Tulsa: Black Wall Street Publishing, 1992); Jewell Parker Rhodes, Magic City (New York: Harper Collings, 1997); a children's book, Hannibal B. Johnson and Clay Portis, Up From the Ashes: A Story About Building Community (Austin: Eakin Press, 2000); and a musical, "A Song of Greenwood," book and music by Tim Long and Jerome Johnson, which premiered at the Greenwood Cultural Center in Tulsa on May 29, 1998.

And more books, it should be added, are on the way. For as of the summer of 2000, at least two journalists were under contract with national publishers to research and write books about the riot and its legacy. Furthermore, a number of Tulsans are also said to be involved with book projects about the riot.

33

Oklahoma newspapers have, not surprisingly, provided the most expansive coverage of recent riot-related news. In particular, see: the reporting of Melissa Nelson and Christy Watson in the Daily Oklahoman; the numerous non-bylined stories in the Oklahoma Eagle; and the extensive coverage by Julie Bryant, Rik Espinosa, Brian Ford, Randy Krehbiel, Ashley Parrish, Jimmy Pride, Rita Sherrow, Robert S. Walters, and Heath Weaver in the Tulsa World.For examples of national and international coverage, see: Kelly Kurt's wire stories for the Associated Press (e.g., "Survivors of 1921 Race Riot Hear Their Horror Retold," San Diego Union-Tribune, August 10, 1999, p A6); V. Dion Haynes, "Panel Digs Into Long-Buried Facts About Tulsa Race Riot," Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1999, Sec. 1, p. 6-, Frederick Burger "The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot: A Holocaust America Wanted to Forget," The Crisis, CVII, 6 (November-December 1999), pp. 14-18; Arnold Hamilton, "Panel Urges Reparations in Tulsa Riot," Dallas Morning News, February 5, 2000, pp. IA, 22A; "The Riot That Never Was," The Economist, April 24, 1999, p. 29; Tim Madigan, "Tulsa's Terrible Secret," Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, January 30, 2000, pp. 1G, 6-7G; Rick Montgomery, "Tulsa Looking for the Sparks That Ignited Deadly Race Riot", Kansas City Star, September 8, 1999, pp. Al, A10; James Langton, "Mass Graves Hold the Secrets of American Race Massacre, " London Daily Telegraph, March 29, 1999; Claudia Kolker, "A City's Buried Shame," Los Angeles Times, October 23, 1999, pp. Al, A16; Jim Yardley, "Panel Recommends Reparations in Long-Ignored Tulsa Race Riot," New York Times, February 5, 2000, pp. Al, A10; Martin Evans, "A Costly Legacy," Newsday, November 1, 1999; Gwen Florio, "Oklahoma Recalls Deadliest Race Riot," Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1999, pp. Al, A9; Ben Fenwick, "Search for Race Riot Answers Leads to Graves," Reuter's wire story #13830, September 1999; Warren Cohen, "Digging Up an Ugly Past," U.S. News and World Report, January 31, 2000, p. 26; Tom Kenworthy, "Oklahoma Starts to Face Up to '21 Massacre," USA Today, February 18, 2000, p. 4A; and Lois Romano, "Tulsa Airs a Race Riot's Legacy," Washington Post, January 19, 2000, p. A3.

The riot has also been the subject of a number of television and radio news stories, documentaries, and talk shows during the past two years. The more comprehensive documentaries include: "The Night Tulsa Burned," The History Channel, February 19, 1999; "Tulsa Burning," 60 Minutes II, November 9, 1999; and, 'The Tulsa Lynching of 1921: A Hidden Story", Cinemax, May 31, 2000.