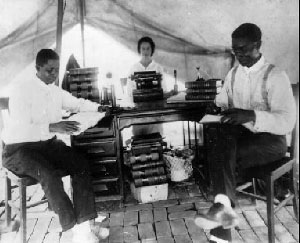

On June 7, 1921, the Tulsa City Commission passed a fire ordinance whose real purpose was to prevent black Tulsans from rebuilding the Greenwood commercial district whre it had previously stood. African American attorney B. C. Franklin, shown at right, helped the legal effort that was successful in overturning the ordinance (Courtesy Tulsa Historical Society).

Assessing State and City Culpability:

The Riot and the Law

By Alfred L. Brophy

The Tulsa riot represented the breakdown of the rule of law.1 As Bishop Mouzon told the congregation of the city's Boston Avenue Methodist Church just after the riot, "Civilization broke down in Tulsa." I do not attempt to place the blame, the mob spirit broke and hell was let loose. Then things happened that were on a footing with what the Germans did in Belgium, what the Turks did in Armenia, what the Bolshevists did in Russia.2 That breakdown of law is central to understanding the riot, the response afterwards, and the decision over what, if anything, should be done now.

This essay assesses the culpability of the city and the state of Oklahoma during the riot, questions that are of continuing importance today. This essay begins by reviewing the chronology of the riot, paying particular attention to the actions of governmental officials. It draws largely upon testimony in the Oklahoma Supreme Court's 1926 opinion in Redfearn v. American Central Insurance Company to portray the events of the riot. Then it explores the attempts of Greenwood residents and other Tulsans who owned property in Greenwood to obtain relief from insurance companies and the city after the riot.

Investigating Tulsa's Culpability in the Riot

This section summarizes the evidence of the city's culpability in the riot. It emphasizes that Tulsa failed to take action to protect against the riot. More important, city officials deputized men right after the riot broke out. Some of those deputies -- probably in conjunction with some uniformed police -- officers were responsible for some of the burning of Greenwood. After the riot, the city took further action to prevent rebuilding by passing a zoning ordinance that required the use of fireproof material in rebuilding.

Greenwood Business District devastated by the race riot (Western History Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

"The Riot"

Questions of Interpretation and Sources

In reconstructing the historical record of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, there are difficulties in interpretation. Questions ranging from general issues such as the motive of Tulsa rioters and was a riot inevitable given the context of violence and racial tension in 1920s Tulsa to specific issues such as whether Dick Rowland would have been lynched had some black Tulsans not appeared at the courthouse, the nature of instructions the police gave to their deputies, and how many people

died can be answered with varying degrees of certainty.3 The record establishes with about as much certainty as on any issue related to the riot that "special" deputy police officers were deeply involved in the burning of Greenwood. Contemporaneous reports establish the shameful record of the hastily deputized police.

Looking for Evidence: The Official Investigations

Important details of the riot are recorded in several contemporary accounts. The 1926 4 opinion of the Oklahoma Supreme Court in Redfearn v. American Central Insurance Company, the least biased of the contemporaneous "official" reports of the riot, demonstrates the close connection between Tulsa's special police and the riot.5 It culminated a two year suit by William Redfearn, a white man who owned two buildings in Greenwood: the Dixie Theatre and the Red Wing Hotel. Redfearn lost both buildings, both were insured for a total of $19,000. The American Central Insurance Company refused payment on either building, citing a riot exclusion clause in the policies. Redfearn sued on the policy and the case was tried in April, 1924. The insurance company claimed that the property was destroyed by riot and the judge directed a verdict for the defendant at the conclusion of the trial. During the trial and subsequent appeal, Redfearn and the insurance company advanced competing stories about the riot. Their briefs present one of the most complete stories of the riot now available.6 They also capture the uncertainty of facts and outcome that is central to a true understanding of history. For we have the written, neatly stylized version of "ancient myth" and the other unwritten, chaotic, full of contradictions, changes of pace, and surprises as life itself.7 As we try to recover the unwritten history, Redfearn's hundreds of pages of testimony are indispensable. It may no longer be possible to think of the events put in motion by the Tulsa Tribune's story on Rowland having any other outcome. However, it is necessary to understand the contingencies, to put ourselves back in the events as they were occurring, and to understand how forces came together in the riot. We now know the broad contours of the riot, but the testimony fills in gaps in specific areas and recovers the chaotic, fearful environment in which black and white Tulsans struggled to prevent violence, even as strong forces, like the ideas of equality and enforcement of the law against mob violence clashed with white views of the place that blacks should occupy. The following account is drawn from those briefs and is supplemented with contemporary newspaper stories.

Curiosity reigned as whites toured the destroyed Greenwood district after the riot (Courtesy Western History Collection, University Of Oklahoma Libraries).

Evolution of the Riot

As best as we can now determine, a crowd of whites began gathering at the Tulsa County courthouse in the early evening on Tuesday, May 31. They were drawn there at least in part by a newspaper story implying that nineteen-year-old Dick Rowland had assaulted seventeen-year-old Sarah Page, a white elevator operator.8 Sometime around 4:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. and certainly by 6:30 p.m., rumors that Dick Rowland would be lynched that evening circulated in the Greenwood community.9 Greenwood residents were becoming more anxious as the evening wore on. William Gurley, owner of the Gurley Hotel in Greenwood and one of the wealthiest blacks in Tulsa, went with Mr. Webb to the courthouse to investigate the rumored lynching. The sheriff told him "there would be no lynching; if the witness could keep his folks away from the courthouse there wouldn't be any trouble." Gurley then went back to report his conversation with the sheriff to the crowd gathered outside his hotel. The crowd was skeptical. "You are a damn liar," said one person. "They had taken a white man out of jail a few weeks before that, and that they were going to take this Negro out." At that point the speaker "pointed a Winchester at [Gurley], and was stopped by a Negro lawyer named Spears."10

At approximately 9:00 p.m., the situation was becoming more heated. William Redfearn, owner of a theater testified that he closed his business about 9:00 p.m. or 9:30 p.m. on the evening of May 31. He closed it because a colored girl came into the theatre and was going from one person to another, telling them something, and he looked out into the street and saw several men in the street talking and bunched up. Upon inquiry as to what was wrong, someone said there was going to be a lynching and that was the reason they had come over there.11 Redfearn went to the courthouse, where someone asked him to go back to Greenwood, to try to dissuade the black residents from coming to town. Despite Redfearn's efforts, he was unsuccessful. When he returned, "there was a bunch of men standing in front of the police station and across the street when he arrived at that place; that there was probably fifty or sixty men in front of the police station.12 The police chief attempted to persuade the blacks to disperse. Gurley told the court about the unstable scene at the courthouse:

That some white man was making a speech and advised the people to go home, stating that the Negroes were riding around with high powered revolvers and guns downtown; that the speech had some effect and the crowd started to disperse, but would soon come back; that while this man was speaking the witness noticed "some colored men coming from Main street; that when the machine was up in front of the courthouse, the people there closed in around that bunch of men, and that when they got mixed up a pistol went off, but the crowd soon dispersed, and he didn't know whether anyone was killed or not.13

Shooting started after the confrontation.14

After the shooting, "hell . . . broke loose," as O.W. Gurley told William Redfearn when they met that night.15 The record is not as clear on what happened immediately after the initial shooting. White witnesses were likely reluctant to testify and few blacks witnessed the next events around the courthouse.

The mob broke into Bardon's pawnshop, looking for guns. Henry Sowders, a white man who operated the movie projector in the Williams' Dreamland Theater in Greenwood, closed up shop around 10:30 p.m. His car had been commandeered by blacks and he was taken back towards the courthouse by a black man. As he passed the courthouse, he was told he "had better get on home to his family, if he had one, or else get some arms, for the thing was coming on."16 The police department's reaction to the events "coming on" was to commission hundreds of white men.17

One of the best descriptions of the unfolding of events came from Columbus F. Gabe, a black man who lived in Greenwood for about 15 years. His testimony at the Redfearn trial preserves the unfolding of the entire riot and thus allows us to reconstruct a picture through a single character. He first heard about the lynching around 6:30 p.m. He went home to pick up a gun, and then he went to the courthouse. When Gabe arrived at the courthouse, there were perhaps about 800 people there and tensions were already running high. Some people were yelling to "Get these niggers away from here." Meanwhile, Gabe was told by a carload of blacks to arm himself. Whites were going to the armory to arm themselves and several carloads of armed blacks headed towards the courthouse. Gabe left the courthouse area, but was still within earshot when the gun that began the riot went off. The next morning, he was ousted from his house by two men. One said to the other, "Kill him," and the other said, "No, he hasn't a gun, don't hurt him," and said, "Get on up with the crowd." He was then taken to the Convention Center.18

Barney Cleaver, a black member of the Tulsa Sheriffs Department, presented similar testimony about the way the forces gathered momentum around the riot. He was policing Greenwood Avenue when he heard rumors of a lynching, so he drove up to the courthouse. According to Cleaver, as the blacks were dispersing, a gun fired and then people began to run away. He stayed at the courthouse until about four o'clock the next morning and then he headed back to Greenwood, where he met about 15 or 20 black men. He told the group that no one had been lynched and that they should go home. Someone then "made the remark that he was a white man lover."19

On the morning of June 1, most black Tulsans who were taken into custody were brought to Convention Hall, on Brady Street. Later, detention areas were established at the fair grounds and McNulty ball park (Courtesy Western History Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

The next morning, a whistle blew about 5:00 a.m., and the invasion of Greenwood began. Gurley left his hotel around 8:30 a.m., because he became worried that it might burn and as white rioters appeared. Gurley stated,

"Those were white men, they was wearing khaki suits, all of them, and they saw, me standing there and they said, 'You better get out of that hotel because we are going to burn all of this Goddamn stuff, better get all your guests out.' And they rattled on the lower doors of the pool hall and the restaurant, and the people began on the lower floor to get out, and I told the people in the hotel, I said 'I guess you better get out.' There was a deal of shooting going on from the elevator or the mill, somebody was over there with a machine gun and shooting down Greenwood Avenue, and the people got on the stairway going down to the street and they stampeded."20

Gurley hid under a school building for a while. When he came out, he was detained and taken to the Convention Center.

The Oklahoma a Supreme Court's Version of the Riot

The Oklahoma Supreme Court's opinion in Redfearn, written by Commissioner Ray, acknowledges the city's involvement in the riot. The court wrote that "the evidence shows that a great number of men engaged in arresting the Negroes found in the Negro section wore police badges or badges indicating they were deputy sheriffs." It questions, however, whether the "men wearing police badges" were officers or were "acting in an official capacity.21 That statement indicates Commissioner Ray's pro-police bias. The case was appealed from a directed verdict against Redfearn, that meant the trial judge concluded there was no evidence from which a jury could conclude that the men wearing badges were officers. Yet, cases involving resisting arrest routinely conclude that a police badge indicates one's authority to arrest. Simply put, if one of the blacks involved in the riot resisted one of the men wearing a badge, he could have been prosecuted for resisting arrest. Commissioner Ray could have insulated the insurance company from liability with the statement that, even assuming the men wearing badges were police officers, they were acting beyond their authority and were thus acting as rioters. Ray's inconsistency in applying precedent suggests that his motive was not a solely impartial decision of the case before him, but the insulation of the police department and Tulsa from liability.

African Americans were detained by many different white's, not only the police or National Guard (Courtesy Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa).

There is substantial testimony in Redfearn's brief, moreover, demonstrating a close connection between the "police deputies" and the Police Chief Fire Marshal, Wesley Bush, stated that when he arrived at the police station sometime after 10:00 p.m.,

the station was practically full of people, and that the people were armed; that there would be bunches of men go out of the police station, but he didn't know where they would go; that they would leave the police station and go out, and come back - they were out and in, all of them, that they were in squads, several of them together.22

The instructions those special deputies received are unclear. According to pleadings in a suit filed by a black riot victim, one deputy officer gave instructions to "Go out and kill you a d__m nigger."23 Another allegation was that the mayor gave instructions to "burn every Negro house up

to Haskell Street."24 Other contemporary reports contain similar allegations.25

Whether they received instructions to "ru[n] the Negro out of Tulsa," as one of the photos

of the riot was captioned or not, many of the rioters wore badges and started fires.26 Green Smith, a black carpenter who lived in Muskogee and was in Tulsa for a few days working on the Dreamland Theater installing a cooling system, testified to the role of the special police during the riot. He awoke before 5:00 a.m. and went to work at the theater, but soon heard shooting. The shooting was heavy from 5:00 a.m. until around 8:00 a.m., and then it let up. But by 9:30, "there was a gang came down the street knocking on the doors and setting the buildings afire." Smith thought they were police. In response to a cross-examination question, how he could know they were police, Smith testified, "They came and taken fifty dollars of money, and I was looking right at them."27 He saw a gang of about ten to twelve wearing "Special Police" and "Deputy Sheriff' badges. "Some had ribbons and some of them had regular stars."28 Smith was arrested and taken to the Convention Center.

The insurance company's brief presents a different story, one that blames Tulsa blacks. But perhaps most telling is the insurance company's argument at the end of the brief, in which the insurance company was arguing that there was a riot and, therefore, they did not have to pay for the losses. There were from a few hundred to several thousand people engaged in the Tulsa race riot. They met at different places including the courthouse, Greenwood Avenue, the hardware store, and the pawn shop. They fully armed themselves with guns and ammunition, with a common intent to execute a common plan, to-wit: the extermination of the colored people of Tulsa and the destruction of the colored settlement, homes, and buildings, by fire.29

|

Statement: L. J. Martin, Chairman City of Tulsa's Executive Welfare Committee "Tulsa can only redeem herself from the country-wide shame and humiliation in which she is today plunged by complete restitution of the destroyed black belt. The rest of the United States must know that the real citizenship of Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime and will make good the damage, so far as can be done, to the last penny." Ellsworth, Scott - Death In A Promised Land, p. 83 |

(Photo Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society).

|

Statement: Alva Niles, President Tulsa Chamber of Commerce Leading business men are in hourly conference and a movement is now being organized, not only for the succor, protection and alleviation of the sufferings of the negroes, but to formulate a plan of reparation in order that homes may be re-built and families as nearly as possible rehabilitated. The sympathy of the citizenship of Tulsa in a great way has gone out to the unfortunate law abiding negroes who have become the victims of the action, and bad advice of some of the lawless leaders, and as quickly as possible rehabilitation will take place and reparations made . . . Tulsa feels intensely humiliated and standing in the shadow of this great tragedy pledges its every effort to wiping out the stain at the earliest possible moment and punishing those guilty of bringing the disgrace and disaster to this city. Minutes, Tulsa Chamber of Commerce Board Meeting June 15, 1921 |

Apportioning Blame to the City

Whatever interpretation one places on the origin of the riot, there seems to be a consensus emerging from historians that the riot was much worse because of the actions of Tulsa officials. Major General Charles F. Barrett, who was in charge of the Oklahoma National Guard during the riot and thus was a participant in the closing moments of the riot, wrote in his book Oklahoma After Fifty Years about the role of the deputies in fueling the riot. The police chief had deputized perhaps 500 men to help put down the riot.

He did not realize that in a race war a large part if not a majority, of those special deputies were imbued with the same spirit of destruction that animated the mob. They became as deputies the most dangerous part of the mob and after the arrival of the adjutant general and the declaration of martial law the first arrests ordered were those of special officers who had hindered the fire men in their abortive efforts to put out the incendiary fires that many of these special officers were accused of setting.30

Several other white men testified about the role of the police. According to testimony found in the Oklahoma Attorney General's papers, a bricklayer, Laurel Buck, testified that after the riot broke out he went to the police station and asked for a commission. He did not receive it, but he was instructed to "get a gun, and get busy and try to get a nigger."31 Buck went to the Tulsa Hardware Store, where he received a gun. Like many other men, Buck was issued a weapon by Tulsa officials. Buck then stood guard at Boston and Third. In the words of the lawyer who questioned Buck, he "went to get a Negro." By that he meant that, if be had seen a black man shooting at white people he would have "tried to kill him." He was "out to protect the lives of white people . . . under specific orders from a policeman at the police department." And the only reason Buck did not kill any blacks was that he did not see any. The next morning he went near Greenwood, where he saw two uniformed police officers breaking into buildings and setting them afire.32

Another witness, Judge Oliphant, linked the police and their special deputies to burning, even murder. The seventy-three-year old Oliphant went to Greenwood to check on his rental property there. He called the police department around eight o'clock and asked for help protecting his homes.33 No assistance came, but shortly after his call, a gang of men -- four uniformed officers and some deputies -- came along. Instead of protecting property, "they were the chief fellows setting fires."34 They shot Dr. A.C. Jackson and then began burning houses.35

Oliphant tried to dissuade them from burning. "This last crowd made an agreement that they would not burn that property [across the street from my property] because I thought it would burn mine too and I promised that if they wouldn't, . . . I would see that no Negroes ever lived in that row of houses any more."36

The record from the testimony of credible whites before the attorney general and in the Redfearn case, in conjunction with General Barrett's book, demonstrate the involvement of the city in the destruction.

State Culpability: The Divided (and Ambiguous) Roles of the National Guard

During the opening moments of the crisis, the local units of the National Guard behaved admirably. They defended the armory against a crowd of gun-hungry whites, then offered their assistance to the police in putting down the riot. However, it is precisely that offer of assistance and their subsequent cooperation with the Tulsa police that calls their behavior into question.

There also is substantial evidence that the out-of-town units of the National Guard -- those who had traveled throughout the night from Oklahoma City -- helped restore order when they arrived around 9:00 am on the morning of June 1. They deserve some of the credit for limiting the loss of life caused by the white mobs that invaded Greenwood. Nevertheless, the local units of the National Guard may have acted unconstitutionally in restoring order. The guardsmen arrested every black resident of Tulsa they could find and then took them into "protective custody." That left Greenwood property unprotected -and vulnerable to the "special deputies" who came along and burned it.

(Courtesy Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University Of Tulsa).

The key questions then become, what was the role of the local units of the National Guard that were present in Tulsa even before the riot broke out and were there throughout the riot? What was the role of the out-of-town units of the National Guard that arrived from Oklahoma City around 9:00 a.m. the morning of June 1?

The local units knew that there was trouble brewing in the early evening of May 31. They closely guarded their supply of ammunition and guns and waited orders from the governor about what to do next. Sometime after 10:00 p.m., following the violent confrontation at the courthouse, the local units, under the direction of Colonel Rooney, went into action and traveled the few blocks from the armory to the police station, where they established headquarters. The soldiers helped to stop looting near the courthouse.37 They then began working in conjunction with local authorities to try to quell the riot. There was consideration given to protecting Greenwood by keeping white mobs out. But such a plan was abandoned in favor of another, which had disastrous consequences for Greenwood. The local units of the Guard systematically disarmed and arrested Greenwood residents, leaving their property defenseless. When the "special deputies" came along in the wake of the Guard, it was a simple task to burn Greenwood property.

After-Action Reports: The Testimony of the Local Units of the National Guard

The National Guard's after-action reports describe their role in the riot using their own words. Two reports in particular suggest that the local units of the Guard -- while ostensibly operating to protect the lives and property of Greenwood residents -- disarmed and arrested Greenwood residents (and not white rioters), leaving their property defenseless, allowing deputies, uniformed police officers, and mobs to burn it.

According to the report filed by Captain FrankVan Voorhis, the police called around 8:30 p.m. to ask for help in controlling the crowds at the courthouse. No guardsmen went to the courthouse until they received orders from Lieutenant Colonel Rooney, the officer in charge of the Tulsa units of the National Guard. Van Voorhis arrived after the riot had broken out at 10:30 p.m., with two officers and sixteen men. They went to the police station, where they apparently began working in conjunction with the police. At 1: 15 a.m. they "produced" a machine gun and placed it on a truck, along with three experienced machine gunners and six other enlisted men. They then traveled around the city to spots where "there was firing" until 3:00 a.m., when Colonel Rooney ordered them to Stand Pipe Hill. At that point, Rooney deployed the men along Detroit Avenue, from Stand Pipe Hill to Archer, where they worked "disarming and arresting Negroes and sending them to the Convention Hall by police cars and trucks."38 Van Voorhis's report details the capture of more than 200 "prisoners." Van Voorhis's men were able to disarm and capture those Greenwood residents without much gunfire. It appears that his men killed no one.

Captain McCuen's men, however, did fire upon a number of Greenwood residents in the process of responding to what the local units of the Guard called a "Negro uprising." Sometime after 11:00 p.m., McCuen brought 20 men to the police station, where Colonel Rooney had set up headquarters. They guarded the border between white Tulsa and Greenwood for several hours. Then they began moving towards Greenwood and established a line along Detroit, on the west side of Greenwood. They began pushing into Greenwood, using a truck with an old (and likely inoperable machine gun on it), probably around 3:00 a.m. McCuen's men, like Van Voorhis's, were working in close conjunction with the Tulsa police. They arrested a "large number" of Greenwood residents and turned them over to the "police department automobiles," that were close by "at all times." Those cars "were manned by ex-service men, and in many cases plain-clothes men of the police department."39 The close connection between the local units of the National Guard and the police department is not surprising. Major Daley, for instance, was also a police officer.40 The Guard established its headquarters at the police station .41 The local units were instructed to follow the directions of the civilian authorities.42 Once they went into operation, the local units took charge of a large number of volunteers, many of whom were American Legion members and veterans of the war.43

Some may argue that the Guard was taking Greenwood residents into protective custody. Indeed, the local units of the National Guard told the men they were disarming, and they were there to protect them.44 Nevertheless, the after-action reports suggest that the Guard's work in conjunction with local authorities was designed to put down the supposed "Negro uprising," not to protect the Greenwood residents.45

McCuen's men did not seem to be working to protect blacks. In fact, after daylight he received an urgent request from the police department to stop blacks from firing into white homes

along Sunset Hill, located on the northwest side of Greenwood. "We advanced to the crest of Sunset Hill in a skirmish line and then a little further north to the military crest of the hill where our men were ordered to lie down because of the intense fire of the blacks who had formed a good skirmish line at the foot of the hill to the northeast among the outbuildings of the Negro settlement which stops at the foot of the hill." The guardsmen fired at will for nearly half an hour and then the Greenwood residents began falling back, "getting good cover among the frame buildings of the negro settlement." As the guardsmen advanced, they continued to meet stiff opposition from some "negroes who had barricaded themselves in houses." According to McCuen, the men who were barricaded "refused to stop firing and had to be killed." It is unclear how many they killed. Later, at the northeast corner of the settlement, " Ten or more negroes barricaded themselves in a concrete store and a dwelling." The guardsmen fought along side civilians, and at this point, some blacks and whites were killed.46

As the guardsmen were advancing, fires appeared all over Greenwood. Apparently, the white mobs followed closely after the guardsmen as they swept through Greenwood disarming and arresting the residents. They fires followed shortly afterwards. In essence, the guardsmen facilitated the destruction of Greenwood because they removed residents who had no desire to leave and appeared more than capable of defending themselves. While the after-action reports are sparse, they create a picture of the local units of the Guard working in close conjunction with the local civilian authorities to disarm and arrest Greenwood residents. It was those same civilian authorities who were later criticized for burning, looting, and killing in Greenwood.

Colonel Rooney, who was in charge of the local units of the Guard, admitted that the Guard fired upon Greenwood residents. However, he claimed that his men only fired when fired upon.47 Rooney's men were lined up facing into Greenwood and they positioned to protect white property and lives. When the Guard heard that blacks were firing upon whites, they moved into position to stop the firing. When the Tulsa police thought that five hundred black men were coming from Muskogee, they put a machine gun crew on the road from Muskogee with orders to stop at the invasion "at all hazards."48 When Colonel Rooney heard a rumor that the five hundred black men had commandeered a train in Muskogee, he went off to organize a patrol to meet it at the station.49 Yet, in contrast, when whites were firing upon blacks who were in the Guard's custody, they responded by hurrying the prisoners along at a faster pace. The Guard seems to have been too busy working in conjunction with civilian authorities arresting Greenwood residents, or too preoccupied putting down the "Negro uprising" to protect Greenwood property.

McCuen concluded that "all firing" had ceased by 11:00 a.m. The reason for the end of the fighting was not that the Guard had succeeded in bringing the white rioters under control. Rather, it was that the Greenwood residents had been arrested or driven out. "Practically all of the Negro men had retreated to the northeast or elsewhere or had been disarmed and sent to concentration points."50

|

H. A. Guess, Black Wall Street Attorney & Riot Survivor "Tulsa Will". . .The question is will Tulsa raise to the emergency and make good the losses which she has visited upon her colored citizens in the upheavel of June 1st, better known as Tulsa Race Riot? Will her broadminded, big-hearted leaders and town and empire builders surrender to the whim of a few political buccaneers and land schemers whose ulterior motive is self-aggrandisement at the expense of the public will, or, will they rush aside some of the cob-webs of legal technicalities and face the issues of facts in a courageious, generous and altruistic spirit that has so signally characterized the triumphal march at the head of modern civilization of the proud Anglo-Saxton race, and proceed to get on foot plans for the rehabilitation of the burned district?. . .What are some of the things that should be foremost in such a program? Reparation. . . will restore confidence of those whose faith has been seriously shaken; will give notice to the outside world that if Tulsa is big enough, strong enough, cosmopolitan enough to match the greatest race riot in American history, she is also generous enough, proud enough, rich enough and possessing enough respect for law and order and disdaining anything that savors of greed, graft and legal oppressions, to fail to do entire justice to a sorely tried people whose accumulations, in many instances, of a life-time, were swept away in a few hours and too, without any fault on their part. It may very well be said by Tulsa's legal advisers that there is no precedent for re-embursement in such cases; that a bond issue and election to make good the losses would be illegal. We answer the race riot was also illegal and, since the damages wrought was also great, some way should be found to make good the loss. There is and should be an adequate remedy to adjust every great wrong. Column, Oklahoma Sun, August 3, 1921

|

Interpreting the Local Units' Actions

There remains the question of how one should interpret the actions of the National Guard's local units. Individuals appear to have been arrested based on race. Some have argued that the Guard took Greenwood residents into protective custody and that they protected lives by doing so. There were simply too few guardsmen to protect all of Greenwood from invasion by white mobs.51 So the question becomes, is it permissible to draw such distinctions based on race in time of crisis? Was it constitutionally permissible to arrest (or take into protective custody) Greenwood residents? Did the local units of the National Guard behave properly? Mary Jones Parrish captured the frustration of Greenwood residents after the riot:

It is the general belief that if [the state troops from Oklahoma City] had reached the scene sooner many lives and valuable property would have been saved. Just as praise for the State troops was on every tongue, so was denunciation of the Home Guards on every lip. Many stated that they [the local guard] fooled [the residents] out of their homes on a promise that if they would give up peacefully they would give them protection, as well as see that their property was saved . . .. When they returned to what were once their places of business or homes, with hopes built upon the promises of the Home Guards, how keen was their disappointment to find all of their earthly possessions in ashes or stolen.52

Parrish's account testifies to the belief among Greenwood residents that the local troops were culpable and the out-of-town units were responsible for ending the riot, or at least for restoring order afterwards.

While in extremely rare instances it is permissible for the government to draw invidious distinctions based solely on race,53 such action must be narrowly tailored. In 1921, the Supreme Court recognized that it was inappropriate for the government (as opposed to private individuals) to segregate on the basis of race.54 The reports of the Guard units based in Tulsa acknowledge that they arrested many blacks, beginning as early as 6:30 a.m. on June 1.55 At that point, much of Greenwood was still intact. It is likely that had the local units not arrested those residents, their homes would not have been vacant and they might not have been burned. In essence the Guard created the danger when they took Greenwood residents into custody.

Much of the United States Supreme Court's law on racial arrests arises out of World War II. Three cases in particular address the constitutionality of drawing distinctions based on race: Hirabayashi v. United States, 56 decided in June 1943, and Korematsu v. United States.57 and Ex Parte Endo, 58 decided on the same day in December 1944. They all addressed the legality of the United States laws regarding Japanese Americans. Hirabayashi, the first of the race cases to reach the United States Supreme Court, addressed the constitutionality of a curfew imposed on Americans of Japanese ancestry living in Hawaii. A majority of the court upheld the racially discriminatory curfew. One concurring justice observed that "where the peril is great and the time is short, temporary treatment on a group basis may be the only practicable expedient whatever the ultimate percentage of those who are detained for cause."59 The concurring opinions were careful to note that distinctions based on race were extraordinarily difficult to justify. They went "to the brink of constitutional power."60 While arrests might be justified upon a showing of immediate harm, they had to be justified. "Detention for reasonable cause is one thing. Detention on account of ancestry is another," Justice William O. Douglas wrote.61 Justice Murphy's concurrence further limited the government's power to detain American citizens without any showing that they posed a threat.62

While the Supreme Court unanimously upheld a curfew imposed upon American citizens on the basis of race, in two cases decided the next year, some justices voted against continued distinctions based on race. In Ex Parte Endo, Mitsuye Endo, an American citizen whose loyalty to the United States was unquestioned, challenged her continued detention in a relocation camp. The United States sought to justify the detention on the ground that there were community sentiments against her and that, in essence, she was detained for her own safety. In rejecting the argument, the United States Supreme Court observed that community hostility might be a serious problem, but it

refused to permit continued detention on that basis once loyalty was demonstrated.63 The most important-and most heavily criticized case of the trilogy was Korematsu, which upheld the forced relocation of Japanese Americans. The court upheld the relocation, with the bold contention that "when under conditions of modern warfare our shores are threatened by hostile forces, the power to protect must be commensurate with the threatened danger."64 The majority opinion acknowledged that the majority of those interned were loyal.65 We now recognize the decision as improper. Indeed, the Civil Rights Act of 1988, that provided $20,000 compensation to each Japanese American person interned during World War II was premised on the belief that Korematsu and the relocation that it upheld was wrong. The act apologized for the relocation and internment and provided some compensation for those affected.

Justice Roberts' dissenting opinion in Korematsu, argued that the relocation was unconstitutional, and recognized that citizens might occasionally be taken into protective custody. At other times, the government can, Roberts acknowledged, "exclude citizens temporarily from a locality." For example, it may exclude citizens from a fire zone.66 But the internments went beyond limited exclusion for the protection of the people excluded and so Roberts thought them improper. Korematsu involved internment "based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty. . .."67

The evidence seems to establish that the local units of the National Guard, in conjunction with police deputies, arrested based on race, not on danger to the Greenwood residents themselves. The fear of Tulsa's police force was that the Greenwood residents were engaged in an uprising. Their response was to disarm and arrest, in some cases taking life to do so. That behavior is suspect even under the majority's opinion in Koremastsu. Under Justice Roberts's dissent, the actions of the local units of the National Guard are even more suspect. There is one other precedent that is important in interpreting the National Guard's actions: the United States Supreme Court's 1909 decision in Moyer v. Peabody. 68 That case arose from a conflict between miners and mining companies in Colorado. The president of the Western Federation of Miners was arrested by the National Guard and detained for several weeks, even though there 'was no probable cause to arrest him. Simply put, he had committed no crime. Colorado's governor explained that there was an insurrection and that he had to arrest Moyer and detain him to put down the insurrection.69 Justice Holmes gave the National Guard, acting under the governor's orders, broad power to arrest in order to put down an insurrection. Holmes refused to allow a suit against the governor for deprivation of constitutional rights, as long as the governor had a good faith belief that the arrest was necessary. It is easier, though, to classify the arrest of one person in Moyer, as justified, than the wholesale arrest of Greenwood residents. Moyer supported limited arrests to stop insurrections. The local units of the National Guard, in conjunction with deputized Tulsa police officers, arrested thousands. In the process -- according to their own reports--they killed an unspecified number of blacks. Such actions are difficult to defend even applying the legal standards of the times.

Newspaper Accounts of the Official Involvement in the Riot

The accounts of the riot as it was unfolding in the Tulsa World show the coordination of the police, National Guard, and white citizens. Some white men were working to arrest "every Negro seen on the streets." Many of those people had at a minimum volunteered their services to the police.70 "Armed guards were placed in cars and sent out on patrol duty. Companies of about 50 men each were organized and marched through the business streets."71 As the Tulsa World stated in an editorial on June 2, "Semi-organized bands of white men systematically applied the torch while others shot on sight men of color."72

The black press presented starker pictures of official involvement in the destruction. An account of Van B. Hurley, who was identified as a former Tulsa police officer, was printed in the Chicago Defender in October 192 1. The account was circulated by Elisha Scot, an attorney from Topeka, Kansas, who represented a number of riot victims. The Defender reported that Hurley, "who was honorably discharged from the force and given splendid recommendations by his captains and lieutenants," named city officials who planned the attack on Greenwood using airplanes. Hurley described "the conference between local aviators and the officials. After this meeting Hurley asserted the airplanes darted out from hangars and hovered over the district dropping nitroglycerin on buildings, setting them afire." Hurley said the officials told their deputies to deal aggressively with Greenwood residents. "They gave instructions for every man to be ready and on the alert and if the niggers wanted to start anything to be ready for them. They never put forth any efforts at all to prevent it whatever, and said if they started anything to kill every b_ son of a b_ they could find."73 Hurley's account is somewhat suspect, but it fits with Laurel Buck's testimony that the police told white Tulsans to "get out and get a nigger."

At a minimum, there was substantial planning by the police for the systematic arrest and detention of Greenwood residents. Fire Marshal Wesley Bush reported that he saw armed men coming and going from the police station all evening.74 The Tulsa Tribune reported that there had been plans to take Greenwood residents to the Convention Center. It is very difficult at this point to reconstruct the instructions from the mayor and police chief to the deputies. That difficulty arises in large part because the city refused to allow a serious investigation of the riot. There are, however, a substantial number of reports of those instructions and the pattern of destruction certainly fits with those reports. Quite simply, it is difficult to explain the systematic arrest of blacks, the destruction of their property, and the timing of the invasion of Greenwood without relying upon some coordination by the Tulsa city government, with the assistance of the local units of the National Guard.75

Many owners of destroyed property took action against insurance companies.

Statutory Liability for City's Failure to Protect

Asking for reparations for the riot does not require us to read our own morality back onto Tulsa at the early part of the century. Many states provided a remedy for the city's failure to protect riot victims in the 1920s. At the time of the riot, for instance, Illinois had a statute providing a cause of action for damage done by riot when the local government failed to protect against the rioters. The Illinois law provided that the municipality where violence occurred was liable to the families of "lynching" victims. It allowed claims for wrongful death up to $5,000.76 The Illinois courts construed "lynching" to include deaths during race riots.77 If the riot had occurred in Illinois, there would have been a right to recover if the police failed to protect the victims. Tulsans knew about the statutes in Illinois and Kansas. They even consulted an attorney from East Saint Louis for help in understanding their legal liability.78

The Aftermath of the Riot: Of Prosecutions, Lawsuits, and Ordinances

As Tulsans began to shift the rubble after the riot, they asked themselves how had such a tragedy occurred, who was to blame, and how might they rebuild. A grand jury investigated the riot's causes and returned indictments against about seventy men, mostly blacks. The city re-zoned the burned district, to discourage rebuilding, as Greenwood residents and whites who owned property in Greenwood filed lawsuits against the city and their insurance companies. The lawsuits, filed by more than one-hundred people who lost property, testify to the attempts made by riot victims to use the law for relief, and its failure to assist them, even after the government had destroyed their property.

The Failure of Reparations Through Lawsuits

Greenwood residents and property owners (both black and white), filed more than one- hundred suits against their insurance companies, the city of Tulsa, and even Sinclair Oil Company, that allegedly provided airplanes that were used in attacking Greenwood. Not one of those suits was successful. One, filed by William Redfearn, a white man who owned a hotel and a movie theater in Greenwood, went to trial and then on appeal to the Oklahoma Supreme Court. Redfearn's insurance company denied liability, citing a riot exclusion clause. The clause exempted the insurance company from liability for loss due to riot.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court interpreted the damage as due to riot-an understandable conclusion, and thereby immunized insurance companies from liability.79 Following the failure of Mr. Redfearn's suit, none other went to trial. That is not surprising. It is difficult to see how anyone could have prevailed in the wake of the Redfearn opinion. They lay fallow for years and then were dismissed in 1937.

The Grand Jury and the Failure of Prosecutions

Just as the legal system had failed to provide a vehicle for recovery by Greenwood residents and property owners, the legal system failed to hold Tulsans criminally responsible for the reign of terror during the riot. The grand jury, convened a few days after the riot, returned about seventy indictments. A few people, mostly blacks, were held in jail. Others were released on bond, pending their trials for rioting. However, most of the cases were dismissed in September, 1921, when Dick Rowland's case was dismissed. When Sarah Page failed to appear as the complaining witness, the district attorney dismissed his case.80 Other dismissals soon followed .81 Apparently, no one, black or white, served time in prison for murder, larceny, or arson, although some people may have been held in custody pending dismissal of suits in the fall of 1921.

The grand jury's most notable action is not the indictments that it returned but the whitewash it. engaged in. Their report, which was published in its entirety in the Tulsa World under the heading "Grand Jury Blames Negroes for Inciting Race Rioting: Whites Clearly Exonerated,"82 told a laughable story of black culpability for the riot. The report is an amazing document, that demonstrates how evidence can be selectively interpreted. It is, quite simply, a classic case of interpreter's extreme biases coloring their vision of events.

The grand jury, which began work on June 7, took testimony from dozens of white and black Tulsans. It operated within the framework established by Tulsa District Judge Biddson. He instructed the jurors to investigate the causes of the riot. Biddson feared that the spirit of lawlessness was growing. The jurors' conclusions would be "marked indelibly upon the public mind" and would be important in deterring future riots.83 It cast its net widely, looking at the riot as it unfolded as well as social conditions in Tulsa more generally.

The grand jury fixed the immediate cause of the riot as the appearance "of a certain group of colored men who appeared at the courthouse . . . for the purpose of protecting . . . Dick Rowland." From there it laid blame entirely on those people who sought to defend Rowland's life. It discounted rumors of lynching. "There was no mob spirit among the whites, no talk of lynching and no arms."84

Echoing the discussions of the riot in the white Tulsa newspapers, the grand jury identified two remote causes of the riot which were "vital to the public interest." Those causes were the "agitation among the Negroes of social equality" and the break down of law enforcement. The agitation for social equality was the first of the remote causes the jury discussed:

Certain propaganda and more or less agitation had been going on among the colored population for some time. This agitation resulted in the accumulation of firearms among the people and the storage of quantities of ammunition, all of which was accumulative in the minds of the Negro which led them as a people to believe in equal rights, social equality, and their ability to demand the same.85

The Nation broke the grand jury's code. Charges that blacks were radicals meant that blacks were insufficiently obsequious. They asked for legal rights.

Negroes were uncompromisingly denouncing of "Jim-Crow" cars, lynching, peonage; in short, were asking that the Federal constitutional guarantees of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" be given regardless of color. The Negroes of Tulsa and other Oklahoma cities are pioneers; men and women who have dared, men and women who have had the initiative and the courage to pull up stakes in other less-favored states and face hardship in a newer one for the sake of greater eventual progress. That type is ever less ready to submit to insult. Those of the whites who seek to maintain the old white group control naturally do not relish seeing Negroes emancipating themselves from the old system.86

Such was the mind set of the grand jury that they thought ideas about racial equality were to blame for the riot, instead of explaining why Greenwood residents felt it necessary to visit the courthouse. Thus, the grand jury recast its evidence to fit its established prejudices. And as it did that, as it confirmed white Tulsa's myth that the blacks were to blame for the riot, it helped to remove the moral impetus to reparations.

Preventing Rebuilding?

Given the context of racial violence and segregation legislation of Progressive-era Oklahoma, it makes sense that one of the city government's first responses was to expand the fire ordinance to incorporate parts of Greenwood. That expansion made rebuilding in the burned district prohibitively expensive. The city presented two rationales: to expand the industrial area around the railroad yard and to further separate the races.87

The story of the zoning ordinance is one of the few triumphs of the rule of law to emerge from the riot. Greenwood residents who wanted to rebuild challenged the ordinance as a violation of property rights as well as on technical grounds. They first won a temporary restraining order on technical grounds (that there had been insufficient notice before the ordinance was passed). Then, following re-promulgation of the ordinance, they won a permanent injunction, apparently on the grounds that it would deprive the Greenwood property owners of their property rights if they were not permitted to rebuild.88

And so, having won one court victory, Greenwood residents were left to their own devices: free to rebuild their property, but without the direct assistance from the city that was crucial to doing so. Now the question is whether the city and state wish to acknowledge that as a debt and to pay it?

(Courtesy Western History Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

Endnotes

1

This brief report on "the riot and the law" is necessarily summary. For a fuller exploration of many of the issues discussed here, see Alfred L. Brophy, "Reconstructing the Dreamland" (2000), available at http://www.okcu.edu/law/P-broph.HTM2

Black Agitators Blamed for Riot, Tulsa World, June 6, 1921.3

There are seven key questions, which need answers in developing a clear picture of the riot: (1) How did Tulsa go from minor event in elevator to attempted lynching?(2) How did Tulsa go from confrontation at the courthouse to riot?

(3) What was the role of the police? That question has several sub-parts:

(a) How many were commissioned as deputies?

(b) What instructions did police give the deputies?

(c) How much planning was there for the attack on Greenwood?

(4) What was the role of the mayor?

(5) What was the role of the National Guard?

(6) What motivated the changing of the fire ordinance and the rezoning of Greenwood to require building using fireproof material? How was that resolved?

(7) Was a riot inevitable? That question has several sub-parts:

(a) Was there planning before the evening of May 31, to "run the Negro out of Tulsa," as some alleged. See, e.g., "The Tulsa Riots", 22 The Crisis. pp. 114-16 July 1921. "Compare Public Welfare Board Vacated by Commission: Mayor in Statement on Race Trouble", Tulsa Tribune, June 14, 1921 (reprinting Mayor T.D. Evans speech to City Commission. June 14, 1921) "It is the judgment of many wise heads in Tulsa, based upon observation of a number of years that this uprising was inevitable. If that be true and this judgment had to come upon us, then I say it was good generalship to let the destruction come to that section where the trouble was hatched up, put in motion and where it had its inception."

(b) Were racial tensions so great that there would have been a riot even without the attempted lynching of Dick Rowland? See Walter F. White, "The Eruption of Tulsa", The Nation, pp. 909-910 (detailing elements of racial tension and lawlessness in Tulsa). See also: R. L. Jones," Blood and Oil", Survey 46, June 1921.

On questions of historical interpretation, where the record is only imperfectly preserved, there are inevitable uncertainties.

4

221 Pacific Reporter p. 929 (1926).5

The other "official" reports, the grand jury report and the fire marshall's report, are less helpful in reconstructing the riot. The hastily prepared grand jury report blamed Tulsa's blacks for the riot. The grand jury report focused blame on "exaggerated ideas of equality." See "Grand Jury Blames Negroes for Inciting Race Rioting: Whites Clearly Exonerated", Tulsa World, June 26, 1921, pp. 1,8 (reprinting grand jury report). The grand jury report, for instance, declared that the riot was the direct result of "an effort on the part of a certain group of colored men who appeared at the courthouse . .. for the purpose of protecting . . . Dick Rowland...." Id. at 1. An indirect cause of the riot was the "agitation among the Negroes" for ideas "of social equality." Id. It is an extraordinary document, which illustrates in vivid detail how an investigation can select evidence, refuse to seek out alternative testimony, and then formulate an interpretation that is remarkably biased in the story it creates.The fire marshal's report cannot be located. There was another investigation, perhaps by a special city court of inquiry. See "Hundred to be Called in Probe", Tulsa World, June 10, 1921. "With the formal empaneling and swearing in of the grand jury Thursday morning the third investigation into the causes and placing or responsibility for the race rioting in Tulsa law week was begun."; "Police Order Negro Porters Out of Hotels", Tulsa Tribune, June 14, 1921. "This action follows scathing criticism of the system that allowed the Negro porters to carry on their nefarious practices of selling booze and soliciting for women of the underworld made . . . at the city's court of inquiry held several weeks ago."

6

Brief of Plaintiff in Error, William Redfearn, Plaintiff in Error v. American Central Insurance Company, 243 P 929 (Okla. 1926), No. 15,851 [hereinafter Plaintiff's Brief].Of the previous historians of the riot, only Ellsworth has even mentioned Redfearn's suit. See Ellsworth, supra note 2, at 135, n. 57. No one has utilized the Oklahoma Supreme Court's opinion or the briefs.

7

Ellison, "Going to the Territory", in Ellison, Going to the Territory, p. 124 (1986). See also Brent Staples, Parallel Time: Growing Up in Black and White, 1994, (exploring ways that life unfolds and the ways that individuals and families perceive, react to, and rewrite that history). Ellison's essay spoke in terms similar to those employed by Bernard Bailyn, whose widely read monograph on Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of Massachusetts on the eve of the American Revolution, presented a sympathetic portrait of the Loyalist, in an effort to present a comprehensive portrait of the coming of Revolution. See Bernard Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson IX, 1974. One hopes that the Redfearn testimony, when combined with a careful reading of the other texts, will enable us to "embrace the whole event, see it from all sides." Id. We might even see "the inescapable boundaries of action; the blindness of the actors-in a word, the tragedy of the event." Id.The competing narratives of the insurance company and Redfearn showed the ways that Tulsans interpreted what happened during the riot and the conclusions they drew from those events. Cf. Judith L. Maute, Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal and Mining Co. Revisited: The Ballad of Willie and Lucille, 89 NW. U. L. REV. 1341, 1995, (exploring in detail the background to an infamous Oklahoma case). Redfearn shows the competing interpretations of the riot's origins even within the Greenwood community itself and the constraints imposed upon the Oklahoma Supreme Court by desire to limit the city's liability. The testimony shows the diversity of opinions in Tulsa and the ways that legal doctrine shapes those opinions.

Those competing interpretations can tell us a great deal about larger Tulsa and American society, much as studies of medicine and law serve as mirrors for society more generally. See, e.g., Edward H. Beardsley, A History of Neglect: Health Care for Blacks and Mill Workers in the Twentieth-Century South VIII, 1987; Eben Moglen, The Transformation of Morton Horwitz, 93 Column. L. Rev. 1042, 1993, (discussing modes of legal history and the reflections on culture they provide).

8

See R. Halliburton, "The Tulsa Race War of 1921", 2 J. Black Studies, pp. 333-57, 1972. (citing story, "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator", Tulsa Tribune, May 31, 1921.9

Plaintiff s Brief, supra note 6, at 44; 47 (testimony of Barney Cleaver); Brief of Defendant in Error, William Redfearn, Plaintiff in Error v. American Central Insurance Company, 243 P 929 (Okla. 1926), No. 15,851 [hereinafter Defendant's Brief] at 74 (Testimony of Columbus F. Gabe).10

Defendant's Brief, supra note 9, at 101 (Testimony of O.W. Gurley).11

Plaintiff s Brief, supra note 6, at 30 (Testimony of O.W. Gurley).12

Ibid.13

Ibid., at 48-49.14

A somewhat different, more detailed version of the confrontation appears in Ronald L. Trekell, History of the Tulsa Police Department, 1882-1990, 1989.15

Plaintiff's Brief, supra note 6, at 48.16

Ibid., at 44.17

Charles F. Barrett, Oklahoma After Fifty Years: A History of the Sooner State and Its People, 1889- 1939, 1941.18

Plaintiff's Brief, supra note 6, at 40.19

Ibid., at 44.20

Defendant's Brief, supra note 9, at 106.21

221 Pacific Reporter, at 931.22

Plaintiff s Brief, supra note 6, at 67.23

Petition in Robinson v. Evans, et al, Tulsa County District Court, No. 23,399, May 31, 1923.24

Ibid.25

See, e.g., Walter F. White, "The Eruption of Tulsa", 112 Nation, June 29, 1921.26

See, e.g., Plaintiff s Brief, supra note 6, at 61. It is important to note that one early criticism was that the sheriff failed to deputize officers to quell fears of a lynching. See "Tulsa in Remorse," New York Times, June 3, 1921. General Barrett "declared the Sheriff could have [pacified the armed men] if he had used power to deputize assistants. The General said the presence of six uniformed policemen or a half dozen Deputy Sheriffs at the county building Tuesday night, when whites bent on taking from jail Dick Rowland . . . clashed with Negroes intent on protecting Rowland, would have prevented the riot.". See also "Tulsa Officials 'Simply Laid Down'," Sapulpa Herald, June 2, 1921. Reporting General Barren's belief that officials could have prevented riot by dispersing both blacks and whites.27

Plaintiff's Brief, supra note 6, at 62.28

Ibid., (emphasis in original). While the Oklahoma Supreme Court referred to the some of the special deputies as sheriff's deputies and some evidence mentions sheriffs deputies, it appears that the police were the only officials who commissioned special deputies. I would like to thank Robert Norris and Rik Espinosa for clarifying this point with me.29

Defendant's Brief, supra note 2, at 207 (emphasis added).30

Charles F. Barrett, Oklahoma After Fifty Years, 1941.31

Testimony of Laurel Buck 30, Attorney General's Civil Case Files, RG 1-2, A-G Case No. 1062, Box 25 (Oklahoma State Archives).32

Testimony of Laurel Buck, supra note L1, at 32. See also "Witness Says Cop Urged Him to Kill Black", Tulsa Tribune, July 15, 1921; "Instruction is Denied by Court", Tulsa World, July 16, 1921, (summarizing Buck's testimony).33

Testimony of John A. Oliphant, at 2, Attorney General's Civil Case Files, RG 1-2, A-G Case No. 1062, Box 25 (Oklahoma State Archives).34

Ibid., at 6.35

Ibid., at 7.36

Ibid., at 8.37

See "Weapons Must be Returned," Tulsa World, June 4, 1921, (asking for return of weapons and threatening prosecution if weapons are not returned).38

Frank Van Voorhis, "Detailed Report of Negro Uprising for Service Company, 3rd Infantry Oklahoma National Guard," July 30, 1921.39

John W. McCuen, "Duty Performed by Company 3rd Infantry Oklahoma National Guard at Negro Uprising May 31, 1921" (undated) Oklahoma State Archives.40

See "Rooney Explains Guard Operation," Tulsa World, June 4,1921; L .J. F. Rooney and Charles W. Daley to Adj. Gen. Bartlett, June 3, 1921 (Oklahoma State Archives) "I asked Major Daley where [the machine gun) had come from and he said 'we dug it up' and I inferred that he meant it was the property of the Police Department of which Major Daley is an officer.".41

Brian Kirkpatrick, "Activities on night of May 31, 1921, at Tulsa, Oklahoma." July 1, 1921, Oklahoma State Archives "After patrols had been established . . . I established your headquarters in the office of the Chief of Police."42

Around 10:00 p.m. on the evening of May 31, Oklahoma's Adjutant General, Charles Barrett, who later criticized the local Tulsa authorities, told Major Byron Kirkpatrick of Tulsa to "render such assistance to the civil authorities as might be required." Kirkpatrick, supra note 41.43

Kirkpatrick, supra note 41 "I assumed charge of a body of armed volunteers, whom I understand were Legion men, and marched them around into Main Street. There the outfit was divided into two groups, placed under the charge of officers of their number who all had military experience, and ordered to patrol the business section and court-house, and to report back to the Police Station at intervals of fifteen minutes."; C. W. Daley, "Information on Activities during Negro Uprising May 31, 1921," July 6, 1921, Oklahoma State Archives "There was a mob of 150 walking up the street in a column of squads. That crowd was assembled on the comer of Second and Main and given instructions by myself that if they wished to assist in maintaining order they must abide by instructions and follow them to the letter rather than running wild. This they agreed to do. They were split up at this time and placed in groups of 12 to 20 in charge of an ex-service man, with instructions to preserve order and to watch for snipers from the tops of buildings and to assist in gathering up all Negroes bringing same to station and that no one was to fire a shot unless it was to protect life after all other methods had failed.".45

Van Voorhis, supra note 38, at 3.46

McCuen, supra note 39, at 2.47

See "Rooney Explains Guard Operation", Tulsa World, June 4, 1921. "None of my men used their rifles except when fired upon from the east. The most visible point from which enemy shots came was the tower of the new brick church. This was sometime just prior to daybreak."48

There were fears, for example, that blacks were coming from Muskogee to reinforce the Greenwood residents: "In response to a call from Muskogee, indicating several hundred Negroes were on their way to the city to assist Tulsa Negroes should fighting continue, a machine gun squad loaded on a truck, went east of the city with orders to stop at all hazards these armed men." "Race War Rages for Hours After Outbreak at Courthouse; Troops and Armed Men Patrolling Streets", Tulsa World, June 1, 1921.49

Ibid. See also Daley, supra note 43. "Upon receiving information that large bodies of Negroes were coming from Sand Springs, Muskogee and Mohawk, both by train and automobile. [sic] This information was imparted to the auto patrols with instructions to cover the roads which the Negroes might in on. At this point we received information that a train load was coming from Muskogee, so Col. Rooney and myself jumped into a car, assembled a company of Legion men of about 100 from among the patrols who were operating over the city, and placed them in charge of Mr. Kinney a member of the American Legion and directed him to bring men to the depot which was done in a very soldierly and orderly manner. Instructions were given that the men form a line on both sides of the track with instructions to allow no Negroes to unload but to hold them in the train by keeping them covered. The train proved to be a freight train and no one was on it but regular train crew."50

McCuen, supra note 39, at 2.51

See, e.g., "Guardsmen at Center of Riot Discussion", Daily Oklahoman, May 23, 2000, (reporting debate over role of National Guard's role in riot).52

Mary Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster, p. 31, (circa 1921) (reprinted 1998).53

See Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333, 1968. Affirming desegregation order in Alabama prison but observing that there might be instances where segregation was necessary to maintain order. The last time the United States Supreme Court upheld overt (non-remedial) racial distinction was Koremastu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 1944. That decisions--and the United States government's willful withholding of evidence showing that such discrimination was unnecessary--became the basis for the Civil Rights Act of 1988. See Eric K. Yamamoto, "Racial Reparations: Japanese Americans and African American Claims", 40 Boston College Law Review 477-523, 1998. 54See, e.g., Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 1917 (invalidating as unconstitutional a zoning ordinance that segregated on the basis of race). While Professor Aoki has recently analyzed the early twentieth century alien laws as important precursors to the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, Keith Aoki, "No Right to Own?: The Early Twentieth-Century "Alien Land Laws" as a Prelude to Internment", 40 Boston College Law Review 37-72, 1998, no one has yet interpreted the internment of blacks during the Tulsa riot, which drew no legal protest, as a testing ground for the idea of internment. See "85 Whites and Negroes Die in Tulsa Riots", supra note at 2. "Guards surrounded the armory, while others assisted in rounding up Negroes and segregating them in the detention camps. A commission, composed of seven city officials and business men, was formed by Mayor Evans and Chief of Police Gustafson, with the approval ofGeneral Banett, to pass upon the status of the Negroes detained."

55

See Van Voorhis, supra note 38.56

320 U.S. 81, 1943.57

323 U.S. 214, 1944.58

323 U.S. 283, 1944.59

320 U.S. at 107.60

Ibid., at 111.61

Ibid., at 108.62

Ibid. at 113.63

323 U.S. at 302-03.64

323 U.S. at 220.65

Ibid., at 218-19.66

Ibid., at 231.67

323 U.S. at 226.68

212 U.S. 78 (1909).69

Ibid., at 85 "So long as arrests are made in good faith and in the honest belief that they are needed in order to head the insurrection off, the Governor is the final judge and cannot be subjected to an action after he is out of office. . .."70

"Race War Rages for Hours After Outbreak at Courthouse: Troops and Armed Men Patrolling Streets, Tulsa World, June 1, 1921. "Thousands of persons, both the inquisitive including several hundred women, and men, armed with every available weapon in the city taken from every hardware and sporting goods store, swarmed on Second street from Boulder to Boston avenue watching the gathering volunteer army offering their services to the peace officers."71

"Race War Rages for Hours After Outbreak at Courthouse: Troops and Armed Men Patrolling Streets," Tulsa World, June 1, 1921.72

"The Disgrace of Tulsa," Tulsa World, June 2, 1921.73

"Ex-Police Bears Plots of Tulsans: Officer of Law Tells Who Ordered Airplanes to Destroy Homes," Chicago Defender, Oct. 25, 1921. See also: "Attorney Scott Digs Up Inside Information on Tulsa Riot," Black Dispatch, October 20, 1921.74

Plaintiffs Brief, supra note 6, at 67.75

See also Walter F. White, 'The Eruption of Tulsa," The Nation, June 29, 1921. Later White published another account of the riot: "I Investigate Lynchings," American Mercury, January, 1929. 76See, e.g., "Act to Suppress Mob Violence," Illinois, Hurd's Revised Statutes, 1915-16 chap. 38, section 256a.77

See, e.g., City of Chicago v. Sturigs, 222 U.S. 323, 1908, (upholding constitutionality of Illinois statute imposing liability on cities for three-quarters value of mob damage, regardless of fault); Arnold v. City of Centralia, 197 Ill. App. 73, 1915, (imposing liability without negligence under Illinois statute, Hurd's Revised Statutes, 1915-16 chap. 38, section 256a, on city that failed to protect citizens against mob); Barnes v. City of Chicago, 323 M. 203 (1926) (interpreting same statute and concluding that police officer was not "lynched").78

"City Not Liable for Riot Damage", Tulsa World, August 7, 1921.79

221 Pacific Reporter, 929, 1926.80

State v. Rowland, Case No. 2239, Tulsa County District Court, 1921.81

See State v. Will Robinson et al, Case No. 2227, Tulsa County District Court, 1921.82

Tulsa World, June 26, 1921.83

"Judge Biddson's Instructions to Grand Jury," Tulsa Tribune June 9, 1921.84

"Grand Jury Blames Negroes for Inciting Race Rioting: Whites Clearly Exonerated," Tulsa World, June 26, 1921.85

Ibid.86

Walter F. White, "The Eruption of Tulsa", The Nation, 909 June 29, 1921. One justice on the Georgia Supreme Court explained the origins of an Atlanta riot in this way: "This one thing of the street car employees being required by their position to endure in patience the insults of Negro passengers was, more largely than any other one thing, responsible for the engendering of the spirit which manifested itself in the riot." Georgia Railway & Elec. Co. v. Rich, 71 S.E. 759, 760 (Ga, 1911).87

See "Burned District in Fire Limits," Tulsa World, June 8, 1921, (reporting the "real estate exchange" organization supported expansion of fire limits, because it would help convert burned area into industrial area near the railroad tracks and would "be found desirable, in causing a wider separation between Negroes and whites").88

"Negro Sues to Rebuild Waste Area," Tulsa World, August 13, 1921; "Three Judges Hear Evidence in Negro Suit," Tulsa World, August 25, 1921. The three-judge panel upheld the ordinance to the extent that it prohibited the building of permanent structures. But it allowed the building of temporary structures. Ibid. The property owners argued that the city was depriving them of their property by such restrictive building regulations and that the restrictions endangered their health. See Petition in Lockard v. Evans, et al., Tulsa County District Court, Case 15,780 paragraphs 6-7, August 12, 1921. Their argument was based, at least in part, on the emerging police power doctrine that the state could regulate to promote health and morality. The petitioners applied a corollary to that doctrine, arguing that the city was prohibited from interfering with that protection. The judges granted first a temporary restraining order against the ordinance in August because there was insufficient notice when it was passed. See "Can Reconstruct Restricted Area, District Judges Grant Restraining Order to Negroes", Tulsa World, August 26, 1921. Then, following re-promulgation of the ordinance, the judges granted a permanent injunction against it, citing the ordinance's effect on property rights. See "Cannot Enforce Fire Ordinance, Court Holds Unconstitutional Act Against The Burned District," Tulsa World, September 2, 1921. The judges' opinion has been lost.